How Japan Saved Tokyo's Rail Network from Collapse (Part 2, 1982-Now)

What does it take to build a rail nirvana?

Japanese National Railways President Takaya Sugiura (L) speaks to staff prior to its privatization at the company headquarters on March 31, 1987 in Tokyo, Japan. On April 1, 1987, Japanese National Railways was dissolved and the privatized Japanese Railways (JR) took over. (Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

In Part 1, I went into detail about Tokyo’s regional rail lines being pushed to its physical limits and the consequent Commuting Five Directions Operation (1965-1982) to rescue five of its most popular lines by adding more capacity. The Commuting Five Direction Operation (通勤五方面作戦, tsukin-gohomen-sakusen) aimed to add rail capacity by adding extra tracks, converting freight rail lines to passenger rail, extending rail lines and creating new rapid lines to help move more passengers especially at peak commute hours. I argue in Part 1 the Commuting Five Directions Operation is the most consequential project in postwar Japanese rail history (not named Shinkansen) and its investments still shape greatly the Greater Tokyo Area.

Part 2 will be less historical and more discursive, exploring the present-day legacy of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. This will not be a straight chronology from 1982 to 2022. I felt there is no clear end marker for the Operation’s impacts. Perhaps one can argue 1982 as the end, when the last extension on the Joban Line was completed. Another may stretch the timeline to 1987, when the public-owned Japanese National Railways (JNR), practically insolvent due to 20+ years of deficits and a debt crisis partly ballooned by the Commuting Five Directions Operation, was privatized under Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone and split into six Japanese Railways (JR) companies. Even more tenuously, the timeline can be stretched to 1998, when the JNR Settlement Corporation, which held JNR’s long-term liabilities, was disbanded and its debt was transferred into the national budget. (AKA Japanese taxpayers paid off the debt)

The five beneficiary lines of the Commuting Five Directions Operation — Tohoku, Chuo, Tokaido, Sobu, and Joban lines — were all transferred during privatization into the JR East Company. JR East, one of six JR companies, oversees the eastern half of the Honshu Island and, most importantly, the Greater Tokyo Area and the even broader Kanto Region. Of the six JR companies, JR East has been the most profitable and successful — and generally what glowing Western coverage of privatized Japanese rail is referring to. (Only three of six JR companies consistently made profit prior to the COVID-19 pandemic)

Rather than a chronological and geographic dive, as in Part 1, I’ve decided to tackle the myriad facets of Part 2 with a quasi-Q&A with myself from Part 1, who left behind this sneak peek to help guide me through a fluid terrain:

In Part 2, I will review the legacy of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. I will look at whether it solved congestion (as explained above, sort of yes), accommodated for rising ridership (as explained above, yes), cut travel time (spoiler: yes), was worth the billions of Yen as investments (spoiler: yes) and whether the Greater Tokyo Area is in better shape for it (spoiler: yes). In a show of potential bravado, I may even go one step further to argue the privatized and very profitable JR East Company, which run all five regional lines, are merely reaping the fruits of its public predecessor sowed decades before its dissolution.

Let’s dive in, one piece at a time.

Impact on Congestion, Part 2

In Part 1, I shared this table created by Yoshimasa Tadenuma at the Transport Policy Research Institute in his 1998 study “Ex-post evaluation of JNR's investment to increase commuting capacity”.1 In the table, he measured congestion capacity of a single line (number of trains x train capacity) and the congestion rate found during a single peak commute hour.

Note on congestion rate (from Part 1): Under a criteria set by the Railway Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 100% congestion rate is every rider in a train car being able to get a seat, grab a hanging strap or hold onto a bar. 250% is defined as “every time the train sways, my body becomes slanted and can’t move, my hands are immobile”

In this table, a few observations stand out. Except Chuo Line, congestion rates on the five lines saw a small decline from 1965 to 1995. The trains remained highly congested during peak hours. But that may be a glass-half-empty read; a positive spin is that every line was able to increase its ridership by at least 50% (Joban Line tripled its peak hour ridership) and still recorded a decline in congestion rate. Tadenuma’s table counters the expected trend of higher congestion rate as ridership increases substantially.

Tadenuma’s 1998 study uses 1995 data, which is now 27 years old. What does congestion and ridership traffic look like in these lines in the pre-pandemic 2010s? The Railway Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism provides a “Congestion rate data” table of all regional rail lines in Japan with data collected in 2019.2 Below is a translated table using Railway Bureau data highlighting all primary and secondary lines impacted by the Operation (Please read footnote for observed concerns I share on this dataset)3

In 1965, the five beneficiary lines — Utsonomiya (Tohoku), Chuo, Sobu, Joban, and Tokaido — recorded a congestion rate between 219% and 288% according to Ministry data. That percentage range represents, when visualized, an average rider during peak rush hour miserably packed into a train car with little to no space to move his or her limbs. By 2019, that level of congestion and rush hour misery have disappeared. Yokosuka Line marked the most congested line at 195%. Ranging between 140% to 190%, this percentage range represents a fairly packed train where commuters may brush shoulders — but have space to read a book or hold onto a stanchion or bar.

Both Tadenuma’s research from 1995 and 2019 Ministry data point in the same direction: congestion rates declined in Tokyo’s busiest regional rail lines during peak commute hours despite increased ridership corresponding to continued population growth in the region. In the 1960s, Tokyo ran as much trains as they could to relieve congestion and hit its physical and operational limits. And so they doubled down on its infrastructure improvements to be able to run even more trains in the long haul. Tokyo succeeded in eliminating the worst congested train experiences and growing its ridership. Tokyo decided to have its cake and eat it too.

Shaving Minutes, Staving Competition

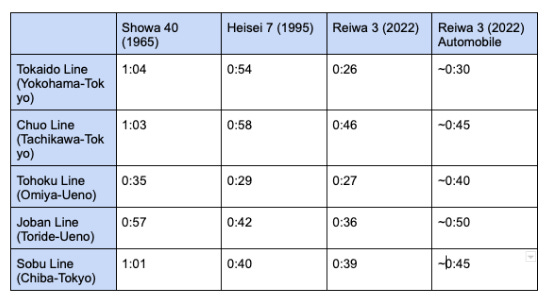

In his study, Tadenuma also outlined travel times between 1965 and 1995 on all five beneficiary lines in its core travel area toward Tokyo Station or Ueno Station in central Tokyo.4

Thanks to the Commuting Five Directions Operation, all five lines saw major time savings in its core route. The Sobu Line (Rapid) saw the biggest time savings; the line connecting Chiba — the major satellite city east of Tokyo — with Tokyo Station in 40 minutes by 1995, saving a whopping 21 minutes compared to 1965 travel times.

Tadenuma writes that the time savings meant an “increase in competitiveness against private railways and automobile traffic…[which] increased the number of passengers transported.”5 He added with improved travel speeds, the “daily mileage of trains increased…it is thought that is now possible to operate the same number of trains with fewer cars.”6 That remained the case through 2022.

When comparing 1995 to 2022 travel times, only the Tokaido Line and Chuo Line saw substantial increases in the same section. This is because they introduced express trains which skips stations at greater speeds and distances than was possible in 1995. Nonetheless, all five lines remained highly competitive to the automobile in time and speed to go from western Tokyo, Yokohama, Saitama or Chiba into central Tokyo. In four of five lines, regional rail is the faster way to travel than a car. Tokyo remains in the minority of cities worldwide which not only has train travel competitive to the automobile but is a superior travel option. 7

Building World-Class Transit Atop World-Class Transit

Creating a superior travel option over the automobile is not only about saving time and money. Convenience and coverage is as important. The Greater Tokyo Area had great infrastructural bones in its regional rail system strengthened by the Commuting Five Directions Operation. But the Japanese National Railways (pre-1987) and JR East (post-1987) continued to build new lines to supplement rider demand in all directions expanding from central Tokyo — even if it created many redundancies with existent lines. I will like to highlight three projects which demonstrate Tokyo’s willingness to build new rail and open new lines to reinforce its regional network and reinvent new possibilities in rail travel:

A detailed map of the JR East regional rail lines, featuring Saikyo Line and Shonan-Shinjuku Line. (By RailRider - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9833484)

First is the Saikyo Line, which opened in 1985. The Saikyo Line connects Saitama (the big satellite city north of Tokyo) with Tokyo. It provides near parallel service with the Utsonomiya Line from Saitama to central Tokyo, connecting at Omiya Station in Saitama and Akabane Station in north central Tokyo. The Saikyo Line is spaced out 2-5 kms away from Utsonomiya Line from Saitama and central Tokyo for the northern leg and then finishes its central Tokyo leg on the Yamanote freight line which runs around the western edge of central Tokyo.

Saikyo Line does not connect to the two great hubs in central Tokyo: Tokyo Station and Ueno Station. Saikyo Line curves around the central districts of Tokyo and Saitama on its western edge. In most other countries, the Saikyo Line may have been considered a waste as it runs so close to the existent central trunk line (Utsonomiya Line) for the first half of its route and then co-opts another popular trunk line (Yamanote Line) for its second half. But perhaps surprisingly, the Saikyo Line has now become one of the Tokyo’s most popular regional lines. It experiences some of the worse overcrowding issues during peak rush hours in all of Tokyo. If anything, Saikyo Line has been combatting its infamy as the rail line with the highest incidents of groping (chikan) of women passengers among all JR East lines, a problem exacerbated during overcrowding.8

Second is the Shonan-Shinjuku Line, which opened in 2001. Partly due to relieve Saikyo Line’s high ridership demand, the Shonan-Shinjuku Line is a true rail operations anomaly. The Shonan-Shinjuku was created without any exclusive right-of-way section to call its own. Again for emphasis, the entire line — a whole regional rail line with a full timetable, local/rapid services and its own rolling stock — runs entirely on the tracks of other regional lines, splicing sections to create new permutations of one-seat rail travel in the Greater Tokyo Area. Its purpose is to provide another north-south regional rail line which connect Saitama, Tokyo and Yokohama together to supplement the Keihin-Tohoku Line, another line which was in need of relief.

Shonan-Shinjuku Line reveals itself as actually two operating lines labeled as one. One runs on the Utsonomiya Line from Omiya Station then switches over to Yamanote Line then on the Yokosuka Line south of Tokyo; the other runs on the Takasaki Line (which runs next to Utsonomiya Line in same right-of-way) from Omiya Station then switches over to Yamanote line then to the Tokaido Line. I cannot help but call the Shonan-Shinjuku the Frankenstein of rail lines, a monster created from different parts not of its own creation. This level of shared rail operations and planning is simply not existent or explored in at least North America.

Lastly is the Ueno-Tokyo Line, which opened in 2015. The youngest project of the three, it is also the shortest spanning only 2.5 kilometers. As the name suggests, this line’s purpose is to create a new line to connect the major hubs of Ueno Station and Tokyo Station. (A North American comparison may be the 42nd Street Shuttle in New York City, connecting Times Square to Grand Central Station)

The Ueno-Tokyo Line is arguably the most important infrastructural work which occurred in central Tokyo in the postwar era. To alleviate congestion on the Keihin-Tohoku Line and Yamanote Line among others, the Ueno-Tokyo Line was planned to build another set of tracks atop the Shinkansen right-of-way between Ueno and Tokyo stations. 9 After six years of construction, the Ueno-Tokyo Line was completed featuring a 1.3 km-long viaduct which rises above the existent rail tracks crammed in the heart of Tokyo. The Shinkansen was never closed during the viaduct’s construction.

The Ueno-Tokyo Line was like a defibrillator to the heart of Tokyo’s regional rail system, redefining the possibilities of rail operations for the Greater Tokyo Area and rejuvenating an already world-class system. JR East concludes in its own postmortem from 2015 that the Ueno-Tokyo Line enabled direct access from the northern Utsonomiya, Takasaki and Joban lines (Ueno was its previous southern terminus) to Tokyo Station further south, and the southern Tokaido Line (Tokyo was its previous northern terminus) to Ueno Station further north. The added capacity “dramatically improved [sic] convenience by shortening travel times due to eliminate of transfers. Furthermore, transportation capacity between Tokyo Station and Ueno Station has been improved substantially, alleviating congestion, especially during the morning rush hour.”10

The Ueno-Tokyo Line, featuring the new viaduct which runs several regional lines (right) over the Shinkansen bullet train (left)

In Part 1, I wrote the Commuting Five Directions Operation endowed “flexibility thanks to added capacity which gives Tokyo, and Japan by large, the steel to build world-class transit atop world-class transit.” In any other city or country in the world, the Commuting Five Directions Operation likely would have an one-and-done transformational project to save any rail network and bring it to modern relevance. If that alone, the work would be impressive. Tokyo however shown the world the upper limits of what a metropolis can do when they continued to expand and reconfigure new possibilities which brings the region ever more tightly. Tokyo in 2022 was not bestowed from the heavens a rail nirvana; it is an end result of 50-plus years of building world-class transit atop world-class transit — in the case of Ueno-Tokyo Line, quite literally atop one another.

Palm and Five Fingers: How Rail Shaped Tokyo’s Suburbs

It is almost laughable to consider Tokyo as anything but an urban environment, but Tokyo is as much a suburban jungle as it is an urban one. In 2012, Tokyo recorded the largest suburban population of any metropolitan area in the world.11 (Perhaps do not apply American expectations of a suburb here) As the Greater Tokyo Area grew from 13 million to 36 million from 1950 to 2010, the core area which the former city of Tokyo — it was merged with surrounding municipalities to create the Prefecture of Tokyo in 1943 — added 3.6 million residents from 5.3 million to 8.9 million. The three surrounding prefectures of Tokyo — Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba — added 15 million residents in the same 60-year span.12

As outlined in Part 1, the suburbanization of Tokyo began as soon as Japan’s postwar economic boom took off in the 1950s, and its outward housing expansion was what precipitated the rail congestion crisis which catalyzed in the Commuting Five Directions Operation. The success of the Operation in reducing congestion rates while accommodating for a growing ridership only accelerated the suburbanization of Tokyo as it became more palatable to endure longer commute times for larger, more suburban housing. Housing around stations by the rail lines became ever more valuable; Tadenuma wrote in his 1998 study “improvement of railroad convenience, such as the easing of congestion and the shortening of the time required…led to an increase in the utility of the location along the railway line.”13

In 2008, a lecture titled “Commuting Five Directions Operation: An Unprecedented Commuter Rail Improvement Project Which Laid Foundations for Today’s Urban Railroads in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area” sought to outline the Operation’s legacy. The speakers included two former and current JR East managing directors, a former JNR chief engineer and an university professor. In the lecture, they agree with Tadenuma’s observation saying the Operation made the five beneficiary lines — and the real estate around them — more enviable and prime for housing and commercial development. Under JR East’s aggressive real estate development in its owned land, stations were transformed into major urban hubs with hotels, shopping malls, housing and commercial zones right next door. The speakers note however that “uncontrolled and endless development of the suburbs brought forth new problems such as longer commuting times.”14 Tadenuma adds in his study the suburban development around the regional rail lines led to an increase of residential space and ration of owner-occupied houses in the Tokyo metropolitan area.15

Both Tadenuma and the 2008 lecture refer to Tokyo’s suburbanization as the “Palm and Fingers” structure as the five beneficiary lines extend out from Tokyo’s core in five different directions, like a human hand. Each finger became a constellation of mini-urban hubs in a densely suburban area. And as more train lines, more development, more housing and more people were introduced, the rail lines increasingly held the Greater Tokyo Area in an ever tighter fist.

“The Cost of Achieving a Future Surplus”

Any major capital work of the size and magnitude of the Commuting Five Directions Operation would generate questions about its cost and prudence. In Japan, it was under heightened scrutiny due to the parallel financial collapse of the Japanese National Railways during the construction of the Operation. The loans taken out to finance the Tokaido Shinkansen and the Operation were the weight which crushed JNR to oblivion by 1987. In 1972, as JNR confronted its financial crisis, JNR officials justified the Operation’s spending as “the cost of achieving a future surplus.”16

The budget of the entire Operation at 313 billion Yen on ground equipment and 70 billion Yen on vehicles in 1965 prices. (716 billion Yen and 114 billion Yen, respectively, in 1995 prices; approximately $6.5 billion and $1 billion in 2022 USD), per Tadenuma.17 18 In his evaluation of the Operation’s investments, Tadenuma sought to quantitatively calculate whether the investments were worth it, and how much.

Tadenuma first outlines two largely accepted financial benefits from the Operation: first, the Operation yielded added capacity to move more passengers. More passengers, more fares, more revenue. Second, the added capacity led to an increase in train operation efficiency with higher train operating seeds. The same number of trains can make more trips, and faster speeds allowed urban regional rail to compete with the automobile.19

But Tadenuma pursued further, attempting to quantify the benefits of all riders and the Greater Tokyo Area societally in financial terms. Tadenuma factors in costs, congestion rate, population along the lines, and traffic volume among numerous quantitative factors — and compares the status quo with an alternate reality where no investments like the Operation was made. Through the prism of his two created realities, Tadenuma calculates the annual total users benefit from the five beneficiary lines improved by the Operation total 1,900 billion Yen ($17.6 billion in 2022 USD) over the 30 years since the Operation began. This figure is an approximation of the total economic and societal profit generated by the results of the Operation. The 1,900 billion Yen annual return is achieved nearly equally from mitigating congested trains and saving travel time on all five lines. The Joban and Sobu Lines — the two lines which a rapid line was created from scratch for faster transportation to/from central Tokyo — marked the highest returns.

Tadenuma also evaluated the financial benefits for each five beneficiary lines by comparing operating income in scenario with and without the Operation. The results were similar to his calculation of annual user benefits, albeit less lucrative with the five lines. He calculates an annual 964 billion Yen in operating income total from the Operation. The Joban and Sobu Lines, again, generated the highest operating income difference. Joban and Sobu lines were most profitable because generalization costs were reduced thanks to a much more efficient rail operation under a new rapid line and the population along these lines soared thanks to the commuting convenience.

Tadenuma ends his study:

It was concluded that the user benefits brought by the Commuting Five Directions Operation were very large and that the project was finally sound…the short-term profitability of the railroad investment project is poor because the increase in transportation capacity due to the increase in population along the railroad lines does not occur in the short term. However, as shown in the study, commuter railroad investment projects contribute greatly to the convenience of railroad use for residents in the region in the long term, and also contribute to the development of the railroad business.

Japanese National Railways, In Memoriam

Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone and U.S. President Ronald Reagan stare out together at a retreat held outside Tokyo in 1983. The two got along very well in their “honeymoon”, and the Japanese media affably called them “Ron-Yas”20

The Japanese National Railways never got to experience the future surplus it predicted back in 1972; JNR continued to operate in the red and sunk into more debt. Its last Commuting Five Directions Operation project was completed in 1982, 17 years after it started. Five years later, JNR was gone.

Most of English-language coverage on the postwar Japanese rail history is focused around 1987 and the privatization of JNR into six JR companies. The simplistic history generally focuses on an eye-watering figure — JNR’s 1986 debt of 19.7 trillion Yen, or $237.8 billion — and one man, Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone.21 In 1983, Nakasone fired JNR’s President after resistance to privatize the behemoth national railways.22 With an unusually heavy-handed approach to economic affairs unseen from past postwar Prime Ministers, Nakasone privatized Japan’s government-owned national railways, national telephone company, and national tobacco corporation during his five-year Prime Ministership. He once repeatedly told his aides, “Unless I reform Japan with my own hands, this country will not see development."23

The 1980s were a heady time for privatization of public services and corporations. While Nakasone was an unconventionally strong-man Prime Minister for Japan, his gusto for privatization was nothing outstanding among its peer world leaders. Ronald Reagan in the United States (who famously got along really well with Nakasone), Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and even the Socialist President Francois Mitterrand of France oversaw privatization of public-owned corporations in their respective countries in the 1980s. Nakasone was not elected into power as some outsider with a mandate for privatization; his Liberal Democratic Party ruled Japan from 1955 (to present day, albeit with minor lapses of losing power) and happily oversaw JNR during its more profitable days.

But such profitable days were long past for JNR. Starting in 1964, JNR went in the red and never recovered. The reasons for JNR’s financial struggles are manifold but there are least four key reasons: 1) the continuous growth of car ownership in Japan crushed national long-distance and rural passenger revenues (not counting Shinkansen); 2) the decline of freight rail traffic, a major moneymaker for JNR; 3) the slowing Japanese economy after booming 50s and 60s compounded JNR’s inability to pay its growing debt; 4) JNR’s board, management and the Japanese Diet were too slow to respond to the debt crisis (the government dismissed the first-ever JNR deficit in 1964 as a “temporary phenomenon”)24

This stands contrary to the conventional understanding of JNR’s demise in the Western world. A narrative prevalent in English-language media since the 1980s paints the tale of two companies: JNR, the fat, bloated and wasteful government-owned enterprise, and JR, the new, shiny, free market paragon of hyper-efficiency. That narrative was hatched in the early 1980s by right-leaning newspaper to cultivate for Nakasone the public opinion support to privatize JNR; one newspaper, the Sankei Shinbun ran a series of special features from February to November 1982 arguing the only way to reform JNR was to crush the so-called" “militant labor unions.”25 One Japanese professor lamented how Sankei Shinbun’s relentless anti-JNR and anti-labor coverage created a bidding war among other Japanese media to follow suit and ratchet up the negativity.26

While acknowledging JNR’s terrible financial record, the current legacy of JNR in the West has become too atrophied and dismissive. JNR was shoddily created in 1949 under the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers to reorganize a key infrastructure network devastated by World War II. In its first 20 years, they rebuilt and electrified much of its national rail lines, built the Shinkansen which earned the awe of the world, and — most importantly for this story — launched the Commuting Five Directions Operation to save Tokyo’s regional rail and consequently redefine the Greater Tokyo Area’s relationship to regional rail. JNR pushed Japan into the 21st century at great financial and institutional cost. It is a shame more credit is not given, at least in its coverage in English.

Meanwhile, the new privatized JR — at least in JR East, which runs Tokyo regional rail lines — were given all the conditions to succeed from its first day on April 1, 1987. 40% of JNR’s total debt was held in a special Japanese National Railways Settlement Corporation (JNRSC); the other 60% were split among the six JR companies. (Until JNRSC too was dissolved and its liabilities folded into the national budget in 1998) JNRSC and JR companies also were allowed to sell surplus land JNR owned to pay off its debts. Unlike JNR, JR companies were also given full license to diversify its non-railway operations into real estate around and atop its stations. Within 30 years of operation, this will translate into JR East’s lucrative real estate success.27

In his 1996 doctorate thesis for the University of Sterling evaluating the policies and processes which culminated in the privatization of JNR, researcher Ian Smith concludes the perceived dichotomy of the failed JNR and successful JR as such:

It is contended that the aura of success — attached to the JNR privatisation by commentators making facile comparison with the public corporation which previously operated the national railway network services — is due, in reality, as much to the prior conditions applied to the privatization process as it is to the tangible results of the new policy for managing the national railway…The procedures introduced to shelve the bulk of the JNR’s debt and thereby to remove the massive interest burden, to cut drastically the labour force of the national railway and to neutralise any union opposition, were the essential elements of a policy initiative designed to conceive an instantly profitable JR Group.28

Closing Thoughts

JNR’s Fourth President Shinji Sogo and his successor Reisuke Ishida ride the Tokaido Shinkansen together. Sogo is the father of the Shinkansen; Ishida is the father of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. The two men helped shape Japanese rail arguably more than anyone in postwar history.

My sentimentality for JNR is not a rebuke against JR.

The JR Group has been an incredible success in both rider experience and in corporate governance. Unlike many transit agencies or companies around the world (especially here in North America), JR’s unmatched freedom in transit-oriented development has enmeshed rail into the core fabric of urban Japanese life. JR’s vertical separation — where each company, divided geographically, holds the keys to operation, infrastructure, maintenance, real estate, services, and more — has allowed for new technologies, like the Suica smart card, and new services like retail and hotels to be experimented and succeed. For JR East, real estate, retail and IT (mainly via Suica) are now major revenue streams for its profits (pre-COVID) — a success formula which is hard to find outside Japan except in a few select Asian cities.

But JR East remains a passenger rail company, first and foremost. Despite real estate, retail and IT’s footprints, 68% of JR East’s fiscal year 2020 revenues (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic ) came from rail transportation.29 The Shinkansen is the biggest source for passenger revenue; the bullet train has been expanded to seven lines total nationwide and three operated by JR East. Its next biggest source are regional lines which connect Tokyo to its suburbs, names likely familiar if you’ve read this far: Tokaido Line, Chuo Line, Keihin-Tohoku Line, Joban Line, Sobu Line. The five beneficiary lines of the Commuting Five Directions Operation are now the backbone of JR East’s transportation success.

To what extent can we attribute JR East’s incredible success to the infrastructural seeds planted and blossomed by its predecessor, the JNR? My answer is: not enough.

As mentioned in Part 1, this two-parter was a labor of love and a labor to find hard answers on exactly how Japan, namely Tokyo, reached the rail nirvana we in North America note from afar with great envy and some befuddlement. Part 1 was dedicated to laying out the material conditions of the near-collapse of Tokyo’s regional rail lines and the granular details of the surgery operation to save it. Part 2 was to unpack the various successes the Commuting Five Directions Operation had on not only the rail lines but Tokyo and its urban fabric.

But Part 2 is also about exploring the oft-forgotten legacy of JNR. During the course of nearly five months of research, translation and writing, I felt extremely compelled by the rise of fall of JNR and the people who steered the behemoth organization. Unlike conventional depictions of JR East as a perfect rail company — its narratives glowing about free market innovations and tinged with Orientalist intangibles — JNR made mistakes (many horrific ones with high body counts), found itself in crises and rose to meet the great challenges. JNR was led by brave men who cared deeply about its mission and tackled its biggest issues to great success — but just not enough to save JNR ultimately from extinction. It was the most human rail company.

Many transit agencies, advocates and officials are at crossroads asking for its own direction in the ever-confounding 21st century. My hope is that this writing can be of use for someone who needs a guide. Hopefully they may be surprised to find that Japan and Tokyo were not given its rail network by divine bestowal but through trial and error, as plain as their own, by men and women as human as their own.

Tadenuma, Yoshimasa. Ex-post evaluation of JNR's investment to increase commuting capacity. 1998. https://www.jttri.or.jp/members/journal/assets/no02-03.pdf

https://www.mlit.go.jp/statistics/details/tetsudo_list.html

A reading guide to the table: the table breaks down each line’s capacity, ridership and congestion rate percentage from a select peak commute hour. For each line, the data is collected between the span between two consecutive stations.

As I was translating this table to English, a few reservations came up. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism did not provide any context to the table on its website. As I had to do more inference than I am comfortable, I am writing them out for full transparency:

There is no methodology available to explain why the data only comes from between two consecutive stations on a line. Always a bad time.

The seemingly arbitrary selection of the stations and timeframes. Most of the selected stations are in central Tokyo, making intuitive sense that a data collector would sample congestion rate at its busiest stretch. Some samples, like the Utsonomiya and Takasaki Lines are in Saitama, the big satellite city north of Japan. I infer their sample is to measure the busy stretch of both branch lines before entering Omiya Station, the major transfer hub in Saitama. We have to infer the random hour starting mark was a purposeful move by the data collectors.

No confirmation that the number of trains (car/unit) is to multiply the trains with the units. I don’t believe the Chuo Line (Rapid) is running a 30-car train. But 10 x 30 = 300 and 44,400/300 = 148 persons per train unit as 100% congestion rate which is a sensible figure.

The inconsistency of the capacity figures between this table and the Tadenuma table above. Tadenuma’s Tokaido Line capacity figure is 79,000; the table below is 35,036. Even if the latter added Yokosuka Line which runs partly along Tokaido Line, the numbers do not square up.

Tadenuma

Ibid.

Ibid.

Note: the 2022 times were compiled from HyperDia, a reputed online trip planner for all Japanese rail lines. The times were hand-selected, and they are express lines which run the designated section at the fastest travel time.

Driving times were hand-selected as the most charitable time on a mid-afternoon weekday time, per Google Maps.

https://web.archive.org/web/20110926213259/http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/komachi/news/20050208sw31.htm

http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr66/pdf/28-37.pdf

Ibid.

http://www.newgeography.com/content/002923-the-evolving-urban-form-tokyo

Ibid.

Tadenuma

Ieda, Hitoshi; Yamamoto, Takuro; Shounou, Shunsuke; Okada, Hiroshi. Commuting Five Directions Operation: An Unprecedented Commuter Rail Improvement Project Which Laid Foundations for Today’s Urban Railroads in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. 2008. https://www.jcca.or.jp/infra70/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PJ-No06.pdf

Tadenuma

Ieda and co.

Ibid.

As footnoted also in Part 1: The Wikipedia page for the Commuting Five Directions Operation show an entirely different budget than the one I use from the Tadenuma report. The reason I stuck with Tadenuma was because it is more recent from 1998; the source for the Wikipedia budget table comes from 1980.

Tadenuma

https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASMCY4RKYMCYUTIL01P.html

https://www.mlit.go.jp/toshi/tosiko/content/001361990.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-12-25-mn-12955-story.html

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20191130/p2a/00m/0na/008000c

Smith, Ian B. The Privatization of the JNR in Historical Perspective: An Evaluation of Government Policy on the Operation of the National Railways in Japan, Vol. 1, Page 261. June 1996. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjgvOjF2o32AhU5JTQIHVBVC_8QFnoECAQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fstorre.stir.ac.uk%2Fbitstream%2F1893%2F29273%2F1%2FSmith_vol1.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2cIWoeetoP00UXj8-B0QKu

Smith, Vol. 2, Page 59. Available in Volume 2 at https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiKnImN3o32AhXiLX0KHbTmA0MQFnoECAgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdspace.stir.ac.uk%2Fbitstream%2F1893%2F29273%2F2%2FSmith_vol2.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0REwocKfKEnSt5pTm1pjsI

Smith, Vol 2. Page 57.

Smith, Vol. 2, Page 274.

Smith, Vol. 2, Pages 329-331.

https://www.jreast.co.jp/investor/factsheet/pdf/factsheet.pdf

"I cannot help but call the Shonan-Shinjuku the Frankenstein of rail lines, a monster created from different parts not of its own creation. "

F-Liner: "Hold my beer..."

This series is great! Nicely researched. It's nice to know about what really went into those lines in Tokyo area. I am from San Jose and lived in Osaka for several years, and now in Korea. Gave up having a car a decade ago and never looked back ;-)

A few other topics related to this series that might be interesting:

What exactly is the degree of 'privatization' of JR? As you mention in passing, JR is not exactly 'private' in the way that Americans might think. How does it differ from the other 'private' lines in Japan, of which there are so many. That is probably another series in and of itself though!

At any rate, thanks for your work on this. Keep it up!