A Tour in Search for the Soul of Seoul

Jongmyo Shrine, Sewoon Sangga, and the uncertain future of the Korean capital

As someone who thinks, writes, and posts a lot about Seoul, I’ve seen an uptick of friends and friendly strangers asking me for travel tips on their next visit to the country. It feels there are more people than ever visiting the South Korean capital, and the numbers agree: Seoul recorded its highest number of foreign tourists in 2025 at 18.5 million visitors.1 Whether it be for the sights, the food, or the lifestyle (and transit, at least those who ask me), Seoul has become a sandbox for tourists from around the world, all each seeking to bring home a piece of authentic Seoul they can claim as their own. And I think most Seoul travel guides miss the mark when suggesting locations for what makes Seoul Seoul.

What makes Seoul Seoul? Like any grand city in the world, it is steeped in history. Don’t let the amnesia-inducing bright neon lights and canopy of high-rise skyscrapers fool you; Seoul is a 600-year-plus city with more transformations in the past century than some cities twice as old have experienced in its lifetime. The Seoul tourism industry likes to package “history” into neatly packaged zones – palaces, museums, or official landmarks — but history is rarely that clean. History lives inside both the symbolic landmarks into improper eyesores, which respectively, describes the two protagonists of this story. They are my favorite buildings in Seoul — and perhaps anywhere in the world. These two locations connect so many threads of local history that simply learning about them can instill a deceptively broad and deep understanding on the topic. And the best part? They are across the street from each other.

The locational pair cannot be further apart in its shape, form, and history: the first is Jongmyo Shrine, a Confucian shrine founded in 1396 which houses the spirits of the kings and queens of the defunct Joseon Dynasty. From above, Jongmyo is an urban forest pockmarked by long wooden buildings centering their own courtyard. The architecture of these buildings from a distance look plain and monotonous in comparison to the colorful bombasts of the palatial structures. The enveloping trees soundproof the urban noise out. At the price of serenity, however, is a relative lack of photogenic spots.

Its direct neighbor is the Sewoon Sangga, a massive complex of brutalist shopping mall buildings which span four wide blocks in a straight north-south line. Sewoon Sangga directly faces Jongmyo to its north, but they share little to nothing in common. Jongmyo’s well-kept, serene paths give way south to a chaotic warren of shops and alleys in and around Sewoon Sangga. Jongmyo’s buildings are single story wooden structures; Sewoon Sangga’s are giant concrete monoliths stretching 17 stories tall, once the tallest in Seoul. The buildings have fallen into serious disrepair thanks to decades of neglect. Locals consider the area a slum. It may well be the least-tourist friendly place in all of Seoul.

Despite being polar opposites in form, function, and contexts, both Jongmyo Shrine and Sewoon Sangga work together as an architectural history textbook on both Seoul and South Korea. And this dual portal may be closing soon, as Sewoon Sangga faces ongoing threats of demolition and redevelopment. In recent months, the two have been the center of a national political scandal amidst a swirl of concern about gentrification, redevelopment, and historical preservation (demonstrating these issues are alive as well in very dense, high-rise-centric cities like Seoul). They are alive with politics, and their mere existence lets the reader travel back in time so they may, upon return, appreciate the current moment better.

This blog, usually focused on mass transit, has spilled a lot of ink on Seoul’s urban history. While this post will be thin on trains and buses, I think this is a necessary addition to the growing Seoul portfolio. I had a chance this summer to briefly visit both sites. I hope I can transmit my enthusiasm and appreciation for these landmarks to you for your next visit to Seoul. To do so, I will be your tour guide today.

Author’s Note

While not the usual transit-focused post, I hope you will enjoy.

I also would like to thank Katharine Khamhaengwong for editing this story. Please follow her at @katharinegk.bsky.social.

You can help support my work at S(ubstack)-Bahn by putting some money in the Ko-fi tip jar.

Jongmyo Shrine and the creation of a Korean Seoul

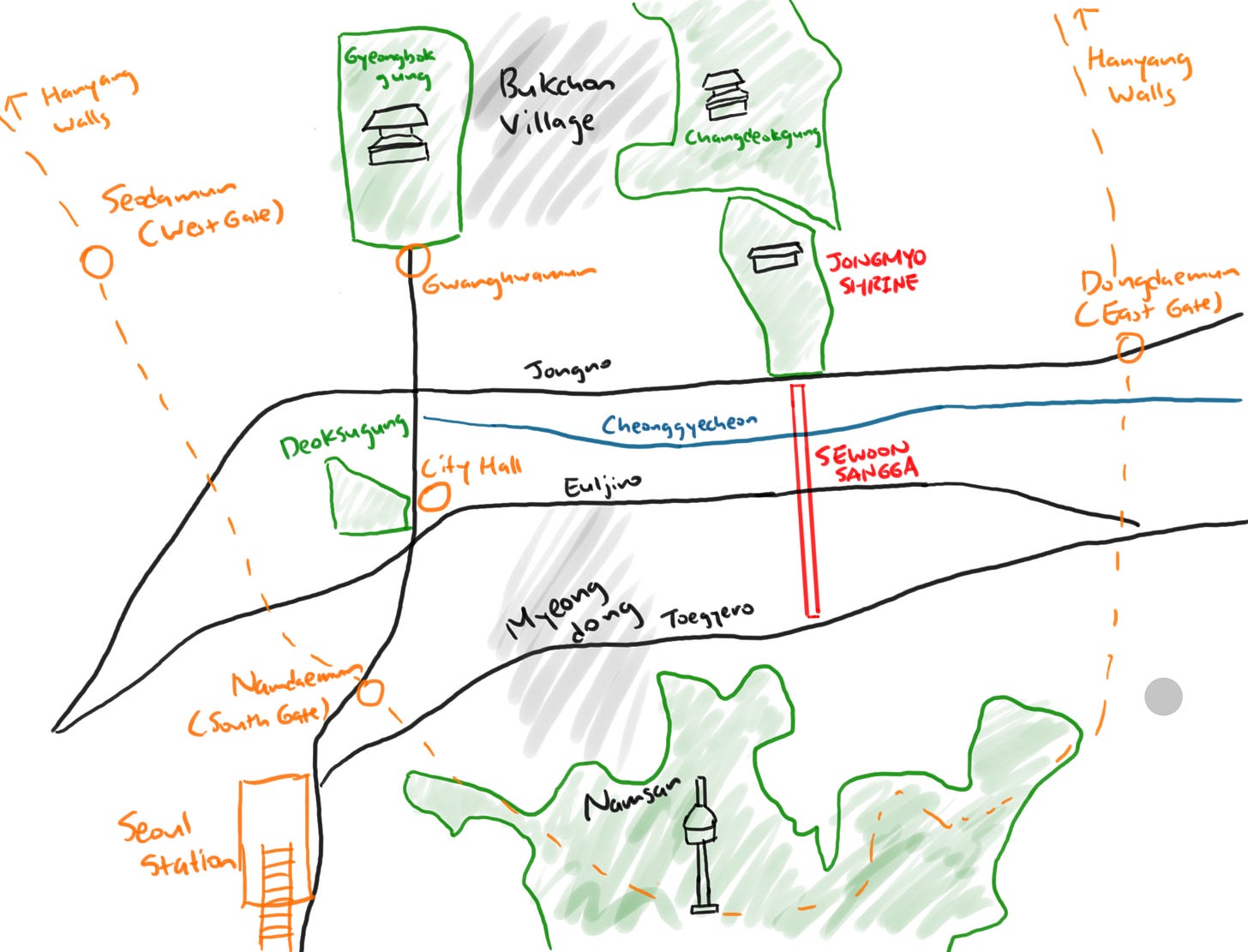

In 1392, General Yi Seong-gye overthrew Goryeo Dynasty, the previous kingdom in the Korean peninsula, and founded the Joseon Dynasty. Eager to rebuild the Korean peninsula in his vision, he dispatched the best geomancers in the land to find him a new city where the invisible energies coursing through the land and water would help bring longevity to his new kingdom.2

They found such a place in a flat valley north of the Han River, surrounded by mountains supposedly radiating with chi energy. Four years later, Yi moved his court to the new capital city of Hanyang, the first of Seoul’s many names, and began building the city according to old feng shui principles dating nearly 3,000 years. One such instruction, from the Rites of Zhou, was “tomb on the left, shrine on the right” (좌묘우사 [左廟右社]).3 From the throne at Gyeongbokgung Palace looking southward, the Sajik Shrine — where kings would pray for good harvests — would be on his right, and Jongmyo Shrine — where the souls of deceased Joseon kings and queens would be housed — to his left.

In Jongmyo Shrine, the kings and queens’ spirits reside inside wooden tablets marked with their names. Several times throughout the year, the Joseon king would pay tribute to his ancestors at Jongmyo, with food, liquor, music and dance especially prepared for the event, known as Jongmyo Jerye-ak. The complex is not a graveyard where the spirits are simply interred; to the Joseon royalty and political elites, the spirits were very much alive and interacting with the living, physical world at Jongmyo. Special spaces, such as a stone-laid “spirit path”, were made through the complex so spirits may walk the area undisturbed. To rule in peace, Joseon kings believed the dead must be held in harmony too.

Above: A short introductory video to Jongmyo Jerye-ak.

Jongmyo Shrine grew in size, undisturbed, for five centuries barring two major interruptions: first, the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592, during which the invaders burned down the shrine and nearby palaces, and second, the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910. Following the 1592 destruction, Jongmyo was rebuilt before the palaces, demonstrating Jongmyo’s centrality to Joseon’s political and religious legitimacy. During the period of Japanese colonization after 1910, the colonial government downsized in scale and significance the practices of Jerye-ak.4 While Jongmyo was left relatively untouched, the Japan reconfigured nearby palaces to their own purposes, building the massive Government-General of Chōsen Building in front of Gyeongbokgung Palace (thereby hiding the palace from view) and turning Changgyeonggung Palace into a zoo and amusement park.5

Jongmyo’s rituals were preserved and now performed once a year by the House of Yi, the former royal family, following independence in 1945 and the Korean War. But the South Korean state’s interest in preserving and restoring Jongmyo and the palaces did not begin in earnest until the year 1995. Two events contributed to the change. First, UNESCO designated Jongmyo as a World Heritage Site, giving the shrine a global validation of historical importance.

Second, President Kim Young-sam, the first civilian president in 30 years, ordered the demolition of the Government-General Building to begin a full, historically accurate restoration of Gyeongbokgung Palace. In a city built on feng shui order, Koreans had long believed the giant, concrete Government-General Building was purposely built to block the chi flow from the mountains in the north onto central Seoul.6 The demolition was symbolized as a modern South Korea throwing off the last shackles of Japanese rule and fully embracing its Joseon roots. Following the demolition, the national government began more rigorously investing in the restoration of the Seoul palaces and Jongmyo Shrine. In 2022, the City of Seoul connected Jongmyo to the palaces to its direct north by burying a busy road and building a park on top.7 In 2025, the Jongmyo restoration was completed after five years of work, its construction materials all manufactured by hand and according to old Joseon-era methods.8

The restoration of Joseon landmarks ushered in a new historic bent in Seoul’s urban renewal work, best exemplified in the Cheonggyecheon freeway removal and stream rehabilitation project of the early 2000s. In 1969, a freeway viaduct was built atop the stream, concealing the stream which once served as the source of potable water for the residents of Hanyang. After 34 years of use, the viaduct was torn down, the stream re-excavated to open-air view, and the surroundings along the stream built to become the walkable tourist destination it is today. The project also included the restoration of three pedestrian bridges from the Joseon era. Archaeological excavations found relics of the pedestrian bridges along the stream and incorporated these centuries-old pieces into the new bridge reconstructions.

At the heart of the Hanyang-era architecture restoration boom is Jongmyo Shrine, the oldest continuous complex of them all. The austere aesthetics of the complex reminds the visitors that this is not a place for the living; the living are here in this world to entertain and sate the spirits through its Jerye-ak rituals. The solemn atmosphere is what made the late, great architect Frank Gehry fall in love with the shrine more than any other building in Seoul, comparing it to the Parthenon in Athens.9 Jongmyo Shrine is the timeless center of Seoul where time can slow and worlds can blend.

The many lives of Sewoon Sangga

If Jongmyo is the spiritual sanctuary for a dead kingdom, then Sewoon Sangga across the street may be the bygone mausoleum for the new global soft power state. While some may be put off by its brutalist, run-down appearance, Sewoon Sangga’s history is so rich it alone can serve as a textbook for Seoul’s postwar history.

Sewoon Sangga is both one and multiple: it is the massive concrete complex which begins immediately south of Jongmyo Shrine, crosses the waters of Cheonggyecheon, and extends southward to the Togye-ro boulevard at the northern foot of Namsan, a mountain in the center of the city. But this complex is broken up into eight lots where eight separate brutalist buildings once towered over the Seoul skyline.10 Seven still stand, and the one gone is the source of the current scandal. Sewoon Sangga is the center of a blue-collar district crammed with small-scale industrial shops — printing presses on Eulji-ro, repair shops and metal workshops near Cheonggyecheon — which began haphazardly congregating here in the 1960s and 1970s. For detractors, it’s the biggest concentration of urban decay in prime Seoul real estate; for supporters, it’s the last place to experience an authentic 20th century Seoul, now at serious risk of extinction by gentrification.

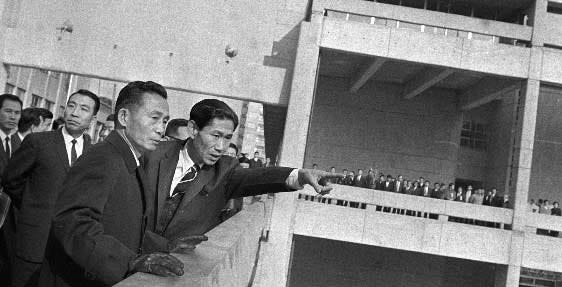

Sewoon Sangga began as a gentrification project in its own right. Before its construction in 1966, the area was replete with slum homes built by thousands of war refugees eking out a living. Nearby neighborhoods were rapidly industrializing without any city planning; Cheonggyecheon in the 1960s – before a freeway viaduct was constructed overhead – was an open sewer for industrial waste dumped from textile sweatshops established along its stream. Pyounghwa Market, where activist Jeon Tae-il would work in the sweatshops and in 1970 self-immolate to protest labor conditions there, was a stone’s throw from Sewoon Sangga. The slum was cleared by the aggressive builder-mayor Kim Hyun-ok, nicknamed “The Bulldozer”, in the mid-1960s and its residents displaced. Kim, with the personal blessing from President Park Chung-hee, would build the first high-rise complex in South Korea.

Sewoon Sangga was the architectural capstone for Park Chung-hee’s vision of state development in 1960s South Korea. A military officer who successfully led the 1961 coup d’etat, Park became president in 1963 and aggressively rallied and coerced the nation to a planned economy focused on rapid export-focused industrialization to propel economic growth. When Park blessed Sewoon Sangga in 1966, South Korea’s GDP per capita was a measly $134 – but Park was eager to stamp South Korea as an economy ready to accommodate westernized haute lifestyles for its own upper class and to signal to the world its arrival. Accordingly, Mayor Kim named the complex Sewoon Sangga (世運商街), the word Sewoon meaning “Channeling the world’s energy.”11

When its first apartments opened for lease in 1967, Sewoon Sangga was the exclusive enclave for Seoul’s wealthiest cosmopolitans, sporting amenities which were not available in the country. The eight buildings each comprised a ground-level parking garage topped with three floors of Western-style department stores, and then a high-rise apartment complex atop that (one of the towers was a luxury hotel). The tallest reached 17 floors, and a deposit for a 160-square-foot apartment was 18 times more expensive than a comparable apartment built for lower-income families at the time.12 Politicians and celebrities flocked to live in Sewoon Sangga; some National Assembly members requested their legislative offices be set up in the complex so they and their families could live, work, and shop without ever having to leave.13

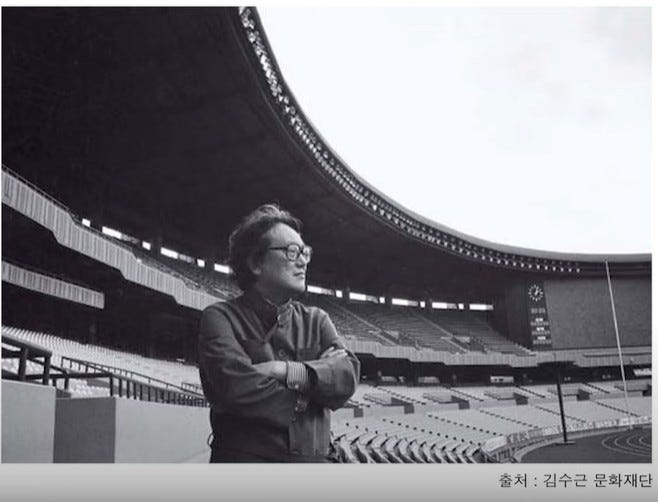

The architect for Sewoon Sangga was the young rising star Kim Swoo-geun, who was in his 30s when he was picked by Mayor Kim to design the complex. Heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, Kim sought to bring the Radiant City to Seoul.14 For Kim, the hallmark feature of the complex would be an aerial walkway on the third floor connecting the eight buildings together; this would provide a straight pedestrian path from Jongmyo Shrine to Namsan Mountain, away from cars and overlooking the city. But such a walkway would not be built for decades. Kim, already considered one of Korea’s most influential architects, died in 1986, at the age of 55, without seeing it completed.

As bright as Sewoon Sangga’s profile shone at its opening in 1967, its luster quickly dimmed in the 1970s. The lack of pedestrian connectivity between the buildings — whether on the ground floor, which had been reserved for parking, or aerially, as Kim envisioned — made Sewoon Sangga hard to navigate for well-to-do shoppers. Soon, the luxury shopping experience moved away to nearby Myeong-dong; then the luxury apartment experience moved away to the Gangnam District south of the Han River. By the 1980s, seedy, black market elements had made their base in the now-neglected Sewoon Sangga complex. It became a flea market for electronics and spare metal parts, often leftovers from deployed U.S. soldiers. Locals used to say, “One can assemble a whole tank with parts produced in Sewoon Sangga.”15 (Other quotes say a missile or a nuclear submarine instead of a tank.) But what sealed Sewoon Sangga’s reputation was its seedy status as the Mecca for all things porn. Despite the military dictatorship cracking down on illicit and indecent materials in the 1980s, every boy and man in Seoul past puberty age seemed to know if they wanted to get their hands on anything pornographic, Sewoon Sangga would have it.16

Sewoon Sangga limped into the 21st century, as their main industries — in secondhand electronics and porn — withered away in the age of the Internet. Beginning in the 1990s, the complex was subject to numerous demolition and redevelopment proposals, including one for a singular 260-floor skyscraper that would be taller than the Burj Khalifa, but no proposals went anywhere until the arrival in 2006 of Mayor Oh Se-hoon.17 (Readers of this blog may be familiar with Oh as the Seoul mayor who ushered in platform screen doors in all Seoul Metro stations –- and his “zero tolerance” stance against disabled protesters in the subway fighting for more accessibility.) In 2008, Oh proposed building a new high-rise mixed-use district with a surface-level greenway through the center of Sewoon Sangga.18 In a show of commitment, Oh demolished one of the eight lots of the complex, the closest one to Jongmyo Shrine. But the global financial crisis soon dried up developer interest. Three years later, Oh resigned following a failed referendum ploy to end free lunch benefits for Seoul schoolchildren.19

Oh’s successor as mayor, Park Won-soon, took the issue of a crumbling Sewoon Sangga in a totally new direction. A strong-willed liberal lawyer with a reputation for fighting for the marginalized, Park eschewed demolition, seeking to preserve Sewoon Sangga in its current form and embark on an urban renewal plan “which places more importance on the prevention of gentrification than development.”20 In 2016, Park funded a renovation and rebranding of the complex as a hip, swanky hub for startups in IT, 3-D printing, robotics, and tech repairs. Video game arcades, a rooftop space for concerts, and a museum of retro electronics opened up shop. The aerial walkway, envisioned by the architect Kim, was also partially completed. Artists and dance studios took advantage of the abandoned office blocks and apartments as spaces for expression and urban exploration. Park’s regeneration efforts won the hearts of visiting western architecture writers during the first Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism in 2017, with one lauding “there are so many exciting implications of what is happening in Sewoon Sangga that it’s hard to know where to start. … All the boring New Urbanism rules are broken.”21

This period turned out be a sweet but short honeymoon due to two catastrophic events in 2020: first, the COVID pandemic, and second, the suicide of Mayor Park a day after he was publicly accused of sexually harassing his female staff. In 2021, Oh was elected back as mayor for his third term. Over the next four years, Oh carefully laid his pieces to finally demolish redevelop Sewoon Sangga, a place he visited in his current term which made him “want to vomit blood” in how little it has changed.22 His plan would ultimately lead to a showdown that recently grabbed the nation’s hearts and minds on what Seoul’s future should look like.

The great battle of Jongmyo

On October 30, 2025, Mayor Oh unveiled a new development project at Sewoon Sangga. He announced that the vacant lot across the street from Jongmyo Shrine would be upzoned significantly for the already selected high-rise developers. The height limit for the northern half of the lot, facing Jongmyo, was increased by 80 percent, to 98 meters, and the southern half, facing Cheonggyecheon, received a 100 percent increase, to 140 meters.23 These jumps in maximum height allowed for at least a 10 to 20 story increase from what Seoul’s zoning codes had previously allowed. This set off alarms in the national government, especially the Korean Heritage Service, the agency responsible for preserving and promoting designated heritage sites — to which Jongmyo is one of its crown jewels. The service argues that the new heights will impede Jongmyo Shrine’s sightlines from ground level and disturb the spiritual serenity the site has provided for centuries.24

The development announcement was years in the making. In 2022, Oh unveiled his “Green Ecological City Re-creation Strategy,” which planned to create new urban parks around Seoul — including at Sewoon Sangga — surrounded by high-rise, mixed-use buildings.25 Oh has argued the park-high rise combination is what Seoul needs to regenerate the area and attract economic growth. The vacant lot by Jongmyo was merely the first lot to get city approval to begin construction. In the 2022 announcement, Oh administration decried the regeneration focus of his predecessor Park as leaving little choice but to seek a bold urban renewal strategy to stem the tide of urban decay.

To achieve big bold actions, small bold steps were required: Oh and the Seoul City Council removed parts of the existing Cultural Heritage Protection Ordinance which required a cultural heritage impact report before approving a high-impact building near a heritage site. The City Council erased these parts and called them broad and excessive regulations; the Korean Heritage Service sued to challenge the removals but the Supreme Court sided with Oh and the Seoul City Council, paving the way for the drastic upzoning of the vacant Sewoon Sangga lot.26

Oh’s announcement sparked a weeks-long news cycle — the verve and televised debates led some commentators to title the war of words between the Mayor of Seoul and the national government “the great battle of Jongmyo.”27 A week after Oh’s press conference, Prime Minister Kim Min-seok, the second-most powerful man in government, visited Jongmyo Shrine to demonstrate his opposition to the upzoning.28 In December, Korean Heritage Service administrator Heo Min reported to President Lee Jae-myung that legislation intended to supersede and prevent Seoul’s upzoning scheme is in the works and likely pass next year at the National Assembly.29 UNESCO also threw its hat in the ring, asking the Seoul Metropolitan Government to suspend the new high-rise plan or risk having Jongmyo’s World Heritage designation stripped.30

The battle between the Korea Heritage Service and Mayor Oh reached fever pitch over two photos. They each published strikingly different three-dimensional renderings on how much shadow the currently planned buildings will cast on Jongmyo Shrine. At a Seoul City Council meeting, Oh held up his own rendering — which shows the high-rises as faraway specks — and asked, “When you see this…do you feel suffocated? Do you feel your chi blocked?”31 The former rendering, however, show the skyscrapers definitively looming over the Jongmyo airspace. (In January, an independent simulation by the Seoul National University Department of Environmental Design found its rendering much closer to the Korea Heritage Service's.)

It’s plausible that in Seoul, with its history of feng shui influences, chi flow could be a serious consideration for planning decisions. After all, in the United States, high-rise plans in urban settings have also been stymied by concerns about shadows or sightlines, too. This episode has been a reminder that even in a city of skyscrapers like Seoul, the argument over whether high-rises can be allowed is never a settled question.

Plans like Oh’s for Sewoon Sangga still can elicit a lot of negative feeling even if they may create thousands of housing units in a long-neglected part of town, in a country where most live in high-rises themselves. The opposition to development has been overwhelming in Korean public opinion; one survey found 69 percent of respondents supported “development restrictions to preserve the landscape and value of a World Heritage site like Jongmyo” versus 22 percent for “the development of high-rises should be allowed to revitalize aging urban areas.”32

Timeliness, or timelessness? Seoul faces a crossroads

All good tours end just before it overstays its welcome, and this tour will leave you, the reader, with some uncertainties surrounding Sewoon Sangga.

The paths of neighbors Jongmyo and Sewoon Sangga are diverging: Jongmyo’s place is secure, likely for centuries to come, but Sewoon Sangga’s fate seems destined for demolition. Even as Oh’s opponents fight back against the increased heights, the opponents have shown no appetite in further renovating the complex, as Mayor Park aimed to do. The choice for Sewoon Sangga seems to be between towering skyscrapers looking down into Jongmyo Shrine or shorter, less imposing new buildings to fill in the area; renovation and regeneration are no longer vogue. When interviewed by the media, shopowners in Sewoon Sangga seemed accepting of their fate, totally exhausted by 30 years of uncertainty about what may come.33

In other countries, a place with Sewoon Sangga’s history might have been treated with far more dignity and respect. As Mayor Park Won-soon tried to salvage, Sewoon Sangga has merit and great potential to educate Seoul’s urban history as a historical landmark. But it seems the buildings are too deteriorated, the political will too atrophied, and the economic headwinds too strong for there to be any hope of actual historical preservation of the area. One wonders if a different fate could have been salvaged had its biggest champion, Mayor Park Won-soon.

As Sewoon Sangga faces an unknown future, the area surrounding the complex, too, faces deep uncertainty as well. South Korea’s rapid economic growth from the 1960s into the 1990s was undergirded by blue-collar manufacturing jobs which, in central Seoul, clustered around hundreds of industrial shops around Sewoon Sangga and Cheonggyecheon.34 These jobs are rapidly disappearing. In many cases, the industrial shop owners and employees are aging out, and there are no younger replacements lined up.

Seoul’s urban history is often colored more by what has been lost than what remains. In the 20th century alone, Seoul was the capital of the dying Joseon Dynasty, the administrative heart of a Japanese colonial state, a bombed out city traded between North and South Korea four times during their civil war, an industrial shantytown generating high economic growth, and then a modern metropolis fit for the 1988 Summer Olympics. Now it is a global city célèbre as South Korean film, television, and music enchant the world. Those who remember the Seoul of previous eras — including myself who opines foolishly for the pre-Asian financial crisis ritzy Seoul and its nowhere-as-good Seoul Metro — often search more for what survived the latest era change than trendy novelty when they revisit. On my last visit, in the dizziness of displacements, I sought groundedness; I found myself in a quiet shrine where time is absent and a decaying mall next door where time is running out.

제 단골 다방도 세운상가에 있어요: https://blog.naver.com/frangdas/223149879101