A Bridge Too Far: Where Japan's National Private Railways Is Failing

Will a Japanese railway company experience a death spiral?

When Japanese train mascots sleep, do they dream of the Shinkansen?

When discussing Japan’s railways, the discussion gravitates towards the two metropolises of Tokyo and Osaka. Deservedly so: it is a fool’s errand to nitpick what are two of the greatest rail metropolises in the world. I have become a belated admirer of Tokyo’s regional rail, and I feel I made good pace in catching up to the fandom by writing 16,000 words in total on the post-WWII history of the system earlier this year.

JR East and JR West — Tokyo and Osaka’s overlord rail corporations, respectively — are nevertheless only two of six companies of equal standing before Japanese law, equally split and created on April 1, 1987. As JR East and JR West soared to railfan superstardom, two brethren JR companies have languished under incredibly difficult times. Despite 35 years of privatization, they wean off massive government subsidies. Signs of a death spiral may be on the horizon.

JR Hokkaido and JR Shikoku are the two smallest and least used JR companies in Japan. Both face similar infrastructural challenges, massive budget deficits and major population declines in their islands. This post will focus entirely on JR Shikoku operating on the island of Shikoku, smallest of the four major Japanese islands. Despite only a bridge ride away from Osaka and Kobe, Shikoku is a world away; its rail system is light-years away.

JR Shikoku has never made an operating profit since its privatization in 1987. Despite continuous help from the national government, JR Shikoku has been plagued by declining ridership, aging infrastructure, and increasing competition from private automobiles and bus companies. COVID only made things much worse. Decades-old passenger rail lines central to the island’s transports may be on the chopping block.

In order to better understand Japanese rail’s future, it is equally important to learn and understand its shortcomings as much as its stellar successes. JR Shikoku’s story — an under-resourced rail company facing dire prospects as its communities are hollowed out — may provide an equally important lesson for those who wonder what a national rail network can be and should be in their home country. As cities worldwide become larger and more central and rural regions are hollowed out, how much do underdeveloped regions deserve its share of the national infrastructure?

Methodology and Background

Upon my research learning more about the political economy of Japanese rail, I found the situation on JR Shikoku and JR Hokkaido rather surprising and very intriguing. While Japanese is not the mother tongue, I used as much as I can all English-language information available on the relevant topics, and translated Japanese articles and documents with the tools available online.

I fully acknowledge that I may have blind spots or inaccuracies in this report easily identifiable to those who are fluent in Japanese or in Japanese rail history. I gave my due diligence to this work but I will happily review any requests to correct any factual inaccuracies and clarify any mistranslation or misunderstanding.

I want to thank the YouTube channel JPRail for being an invaluable resource to this study. This post would not be possible without his videos, “Can JR Shikoku survive? The critical situation of railways in Shikoku” and “The Shikoku Shinkansen Plan: The last resort for JR Shikoku to survive”. I would like to say a special thank you to the channel and its creator, Takeshi.

Shikoku: An Island with Four Faces

In Japanese mythology, Shikoku was the second of eight main islands in the Japanese archipelago created by two Shinto gods. The island was birthed as four faces in one body according to mythology; the current-day name of the island, Shikoku (四国), translates to “Four Countries”.1

Shikoku has always been defined by its four prefectures: Ehime in the northwest; Kagawa in the northast; Tokushima in the east; and Kochi in the south. A rugged mountain range runs through the middle of the island. The four big cities in the island – one in each prefecture – are on the coast. The biggest city on the island is Matsuyama (in the northwestern Ehime) at just over 500,000 people. Its roads for both car and rail are almost entirely ring-shaped with little infrastructure cutting through the mountains.

Shikoku is an island sandwiched between the larger Honshu and Kyushu islands, separated by the Seto Inland Sea. Its southern coast faces the Pacific Ocean. At its closest points, Shikoku is only a 15 mile (25 kilometer) car ride from Honshu and a 18 mile (30 kilometer) ferry ride from Kyushu. Despite the proximity, Shikoku have historically remained the quiet backwater region of western Japan, relatively isolated and underdeveloped. World-renowned cities like Kobe are only a 60 mile drive from the island’s northeastmost town of Naruto.

The island of Shikoku and its cities and railways. Courtesy of Wikitravel.

The Seto Inland Sea — known for its scattered islands and dangerous straits — has been a major barrier for the infrastructural integration of Shikoku until only the 1970s. Three bridges (more like systems of archipelago-connecting bridges) connect Shikoku and Honshu together. Only one carry both cars and rail: the Seto Ohashi Bridge was completed only in 1988 and connects five small islands between Shikoku and Honshu. The bridge is one of the great engineering marvels in modern Japan and comes with a dark history. Plans for the ambitious bridge only commenced until after the 1955 Shiun Maru ferry disaster, when the Shiun Maru ferry collided with another ferry in thick fog in the Seto Island Sea. 168 people died, most of which were children who were traveling via ferry for a field trip.

(Author’s note: as noted in my JNR Part 1, Japan recorded a series of high-fatality rail or ferry accidents in its first twenty years of postwar reconstruction. Shiun Maru was one of Japan’s most traumatic. Shiun Maru resonates with me personally due to its eerie similarities with the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea in 2014. Photo is from the Shiun Maru disaster)

Rail in Shikoku has been on the island almost as long as Japan had rail. The first rail lines in Shikoku were opened in the 1880s and are still in active use. Of JR Shikoku’s nine main intra-island rail lines, the youngest was opened in 1920. In 1988, the Honshi-Bisan Line was opened to provide rail service over the Seto Ohashi Bridge between Honshu and Shikoku. Both JR West (which oversees western Honshu rail network) and JR Shikoku co-manages the Honshi-Bisan Line.

The polycentric rail network in Shikoku lends to no urban centers of gravity where a central rail station can exist. This is opposite to all other islands in Japan, including Hokkaido whose JR company is also struggling. Hokkaido’s capital Sapporo is the sole metropolis of the northern island, and JR Hokkaido’s rail service has increasingly centralized the network around Sapporo. This is impossible to do in Shikoku, as all four prefectures often jockey each other for regional superiority and limited resources while insisting JR Shikoku maintain its service in full in their territory. This is why only two rail lines in Shikoku – tallying less than 9 miles of rail – have been closed in the last 50 years, despite all lines being vastly unprofitable.

No issue is more existential to JR Shikoku than the fact the island is losing people rapidly. From 1987 to 2019, Shikoku lost nearly a half million people from 4.23 million to 3.76 million. By 2030, Shikoku expects to lose another quarter million people. While Japan as a whole is facing a shrinking population due to low birth rates and extremely strict immigrant laws, the double whammy of depopulation and the hollowing out of rural areas and small towns has ravaged Shikoku’s domestic economy, tax base and customer base.

The famous Shimonada Station in Shikoku. The railway station by the sea is a popular tourist spot. Courtesy of Government of Japan’s Public Relations Office

JR Shikoku in the Red

In fiscal year 2019, JR Shikoku generated 28 billion Yen ($219.4 million) in operating revenue. However, they also expensed 41.1 billion Yen ($322.1 million), creating a 13.1 billion Yen deficit ($102.7 million) for the fiscal year. 2

A 13.1 billion Yen deficit was one of the worst deficits JR Shikoku recorded in its 35-year-old history. Between 1987 and 2011, JR Shikoku recorded only two years with a worse deficit.3 Since being splintered off from the defunct public-owned Japanese National Railways in 1987, JR Shikoku has never broken even.

Despite maintaining a nearly identical rail network for over a century, through nationalized and privatized rail agencies, JR Shikoku is bleeding money because their ridership remains undersized. In FY 2019, JR Shikoku registered 44,871,000 rides total – or 122,934 riders a day.4 In comparison, JR East registered 17.9 million riders a day in 2019. Compared to its own ridership in 1989, JR Shikoku’s ridership has seen decreases on all its lines.5

JR Shikoku’s 122,934 daily ridership – again, for the entire island before the COVID-19 pandemic – is comparable to JR Kyushu’s busiest station (Hakata Station), JR West’s fifth busiest station (Sannomiya Station in Kobe) and JR East’s 27th busiest station (Kashiwa Station in Chiba). Even Sapporo Station, by far JR Hokkaido’s busiest station, is not far behind the total Shikoku daily ridership at 99,593 daily riders. As a matter of record, JR Shikoku’s busiest station at Takamatsu registered 12,965 daily riders.6

In an island of decreasing population, JR Shikoku is also contending with the growth of private automobile use and emergence of an interurban highway bus network owned by private companies. As Shikoku’s rail network has remained stagnant since the construction of the Honshi Bisan Line, local and national governments expanded the Shikoku Expressway from just 11 km in 1985 to now more than 500 km, connecting the island with car highways.7 Private bus companies have taken advantage to provide fast, direct connections from Shikoku’s cities and towns to cities outside the island like Osaka and Tokyo — places where direct rail connections are unavailable.

In the 2010s, JR Shikoku pivoted its business model, catering itself as a tourism-focused rail network service. Catering toward native tourists and increasingly foreign tourists, JR Shikoku have made an impressive reputation for its vintage tourist trains like the Iyonada Monogatari sightseeing train through its western coast. JR Shikoku expanded the luxury tourist train experiences to three lines until the COVID-19 pandemic.

A promotional photo of the Iyonada Monogatari tourist train in Shikoku. Courtesy of Shikoku Tours.

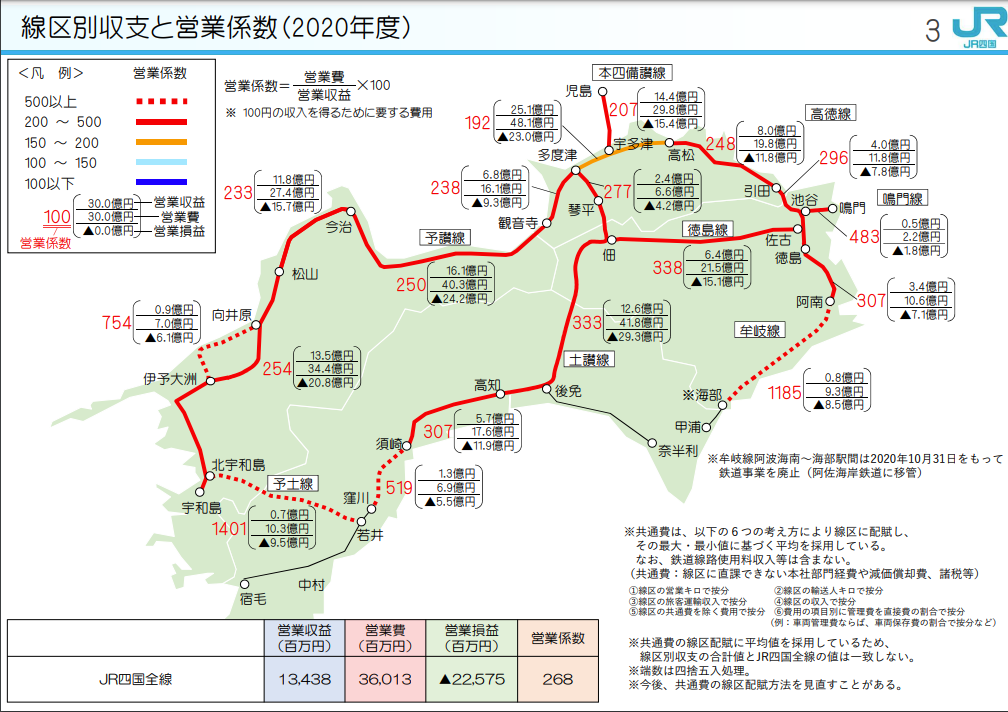

The pre-pandemic success with tourism has not led to windfalls to balance the books. Operating ratios (how much Yen it costs to generate 100 Yen in profit) before the pandemic showed all rail lines except the Honshi Bisan Line — the only route connecting to Honshu — were unprofitable. Even the segments where tourist trains like the Iyonada Monogatari failed to break even.8

The pandemic has also poured gasoline on a simmering money fire, with every line — including the Honshi Bisan Line — costing at least twice the operating revenue generated.

The operating ratio of all JR Shikoku lines in the fiscal year 2020. A rail line making profit would have an operating ratio of under 100, with a blue line. There is no profitable rail line in Shikoku. Courtesy of JR Shikoku’s “About announcement of line distinction balance and operating ratio” report from May 2022

JR Shikoku has never eliminated a single rail line in its system. So how is JR Shikoku staying afloat?

A Government-owned Railway by any other name?

In the 1980s, the Japanese government underwent a seismic privatization of the government-owned Japanese National Railways to help resolve JNR’s catastrophically huge long-term debt of 37.1 trillion Yen ($290 billion!). The reasons for how the debt got so big are manifold, including JNR’s eagerness to take out massive loans to construct the Shinkansen and the Commuting Five Directions Operation. (Read Part 2 for more)

The government led by neoliberal Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone dissolved JNR and replaced it with six independent, privatized JR companies (seven if including JR Freight). Unlike in other countries which underwent rail privatization, Japan went with vertical separation to allocate assets, liabilities and responsibilities; the companies were determined and set up geographically rather than by specializations or operations.9

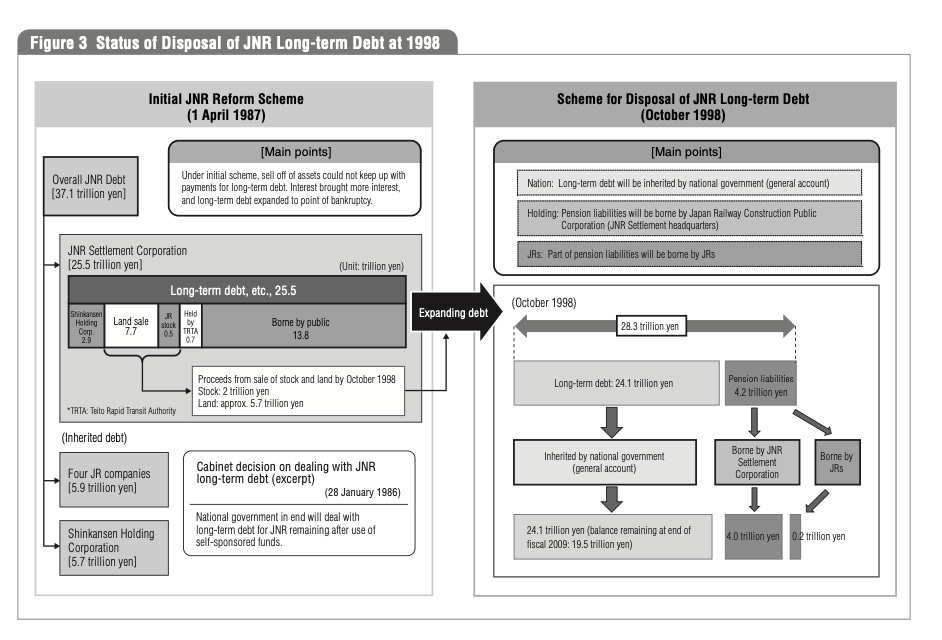

As JNR was dissolved, the Japanese government focused on selling off JNR-owned land and assets to reduce liabilities. They also contained the long-term debt by creating the JNR Settlement Corporation in 1987 to hold 25.5 trillion Yen of inherited debt and pay it off over time. In 1998, the Japanese government gave up this scheme, disbanded the JNR Settlement Corporation and took over 24 trillion Yen into its national budget where taxpayers became liable for payment.10

The Status of Disposal of JNR Long-Term Debt at 1998 table, created for the report “Assessment of Success of 1987 Railway Reforms and Future Issues” by researcher Taro Kobayashi

The splintered JR companies took over a fraction of the total long-term JNR debts — but not all JR companies. JR East, JR Central, JR West, JR Freight and the Shinkansen Holding Corporation took over 11.6 billion Yen of the debt burden, as the Japanese government believed the Honshu-centric four companies were capable of fully paying off its share of debt burden. JR Kyushu, JR Hokkaido and JR Shikoku were not deemed as such.

In addition to no debt burden, the three small JR companies received heavy government subsidies. The Japanese government expected budget deficits from Day 1 for JR Kyushu, JR Hokkaido and JR Shikoku and created in 1987 the Management Stabilization Fund, a government-owned account set up to yield interest that would offset any business losses.

Due to a stagnating Japanese economy and subsequent low interest rates, the Management Stabilization Fund was unable to generate the interest to offset any deficits for JR Shikoku and its two struggling siblings. In 2011, the Japanese Diet amended the law around the fund to allow the Japanese Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency (JRTT) — an independent administration which oversees construction, administration and shareholding among others — to be able to issue special bonds, subsidies and interest-free loans to the three companies. From the amendment, JR Shikoku received 180 billion Yen of virtually free government money to keep trains running.11

In fiscal year 2019, JR Shikoku received 6.8 billion Yen from the Management Stabilization Fund and 3.5 billion Yen from the special bonds. Despite more than 10 billion Yen of government help in addition to its operating revenue to patch its 13 billion Yen, JR Shikoku was left with a 2 billion Yen hole at the end of the fiscal year.

Charts of JR Hokkaido, JR Shikoku and JR Kyushu’s operating profit and loss and Management Stabilization Fund subsidies per year from 1987 until 2011. Charts are found in the report “Assessment of Success of 1987 Railway Reforms and Future Issues” by researcher Taro Kobayashi

But not all struggling JR companies are alike. JR Kyushu received Management Stabilization Fund help until the mid-2000s when its margins began to improve significantly and become profitable. Despite a dip back in the red during the 2008 Recession, JR Kyushu became profitable enough to receive the green light to go completely privatized in 2016 and sell shares to stockholders. JR Kyushu pursued aggressively investments in real estate and hotels from the 1980s and after a generation, JR Kyushu began drawing massive dividends from these non-transit operations. The opening of the Kyushu Shinkansen in 2011 accelerated JR Kyushu’s growth as a fully profitable company. It became the third major island to become integrated in Japan’s high-speed rail network. 12

After the Kyushu Shinkansen opened for service, only Shikoku remains without a Shinkansen among the big four islands.

Looking for a Silver Train Bullet: JR Shikoku’s troubling future

I would highly recommend watching this video on the three proposals of a Shikoku Shinkansen by JPRails.

The Covid-19 pandemic in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 devastated all six JR companies’ coffers as rail ridership dropped precipitously. But no JR company was impacted more than JR Shikoku who even before the pandemic had no wiggle room for failure. JR Shikoku’s heavy dependence on tourist rail riders dried up overnight, and its stagnant domestic ridership fell even further.

In fiscal years 2020 and 2021, JR Shikoku recorded 16.5 billion and 18.3 billion Yen in operating revenue, respectively, falling precipitously from its 2019 revenue of 28 billion Yen. Deficits ballooned 22.6 and 20.2 billion Yen for 2020 and 2021 each, respectively, nearly doubling the deficit from 2019. In December 2020, the national government considered providing JR Shikoku with a 60 billion Yen in one-time financial assistance to be used for the next ten fiscal years. 13

As ridership very slowly returns back to pre-COVID levels, JR Shikoku have been incrementally improving service and amenities, such as restoring the luxury tourist train back to full service and working with private bus operators on the south coast to improve regional coverage and frequency. But JR Shikoku needs a transformation, not a patch. And in Japanese rail parlance, big transformation usually come in the form of a Shinkansen.

Currently, seven Shinkansen lines are in operation with four expansions under construction and three expansions in the planning phase. Shikoku is not involved in any of the plans. To amend this, JR Shikoku, the four prefecture governments of Shikoku and local business community banded to promote the conception of a Shikoku Shinkansen in 2017.

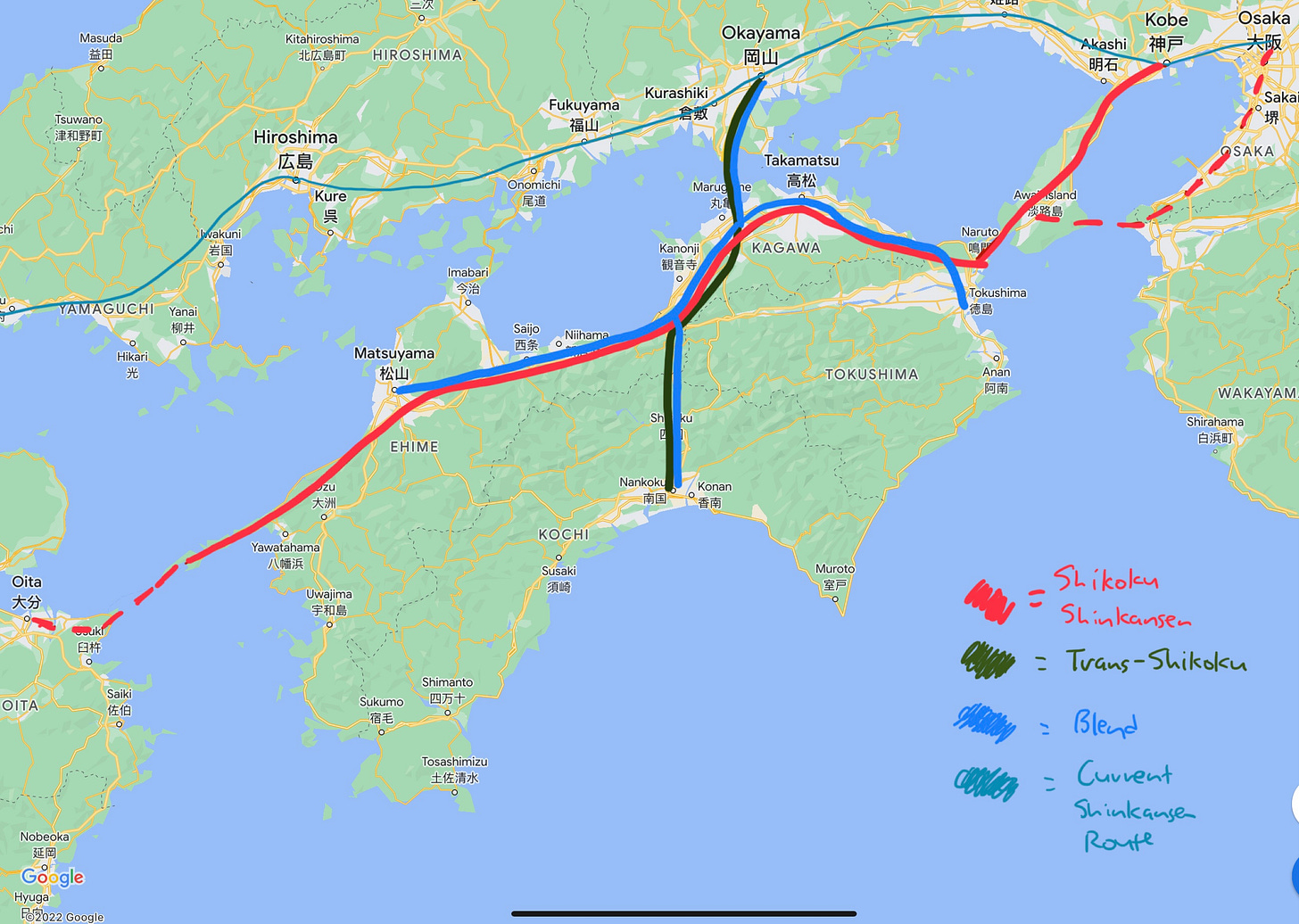

Three ideas have been proposed for a Shikoku Shinkansen. As expertly laid out by JPRail, the following proposals are as such:

A hand-drawn map of the three potential routes of Shikoku Shinkansen. Red line = Shikoku Shinkansen; Dark green line = Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen; Blue line = Blend; Turquoise line = Current Shinkansen route

Shikoku Shinkansen

Despite the generic name, Shikoku Shinkansen is the most ambitious plan of the three. The plan is to connect Osaka and Kobe to Shikoku via Awaji Island: the Shinkansen will cross into Shikoku through its northeastern tip near the town of Naruto and run through the island on its northern half by connecting to Takamatsu and Matsuyama. The potential lies for the Shikoku Shinkansen to cross into Kyushu Island via the Hoyo Strait and connect to the existent Kyushu Shinkansen.

Feasibility of the Osaka-Naruto leg of this plan has good news and bad news: while the Onaruto Bridge between Naruto and Awaji Island has a second deck where railroads can be laid, the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge between Awaji and Kobe does not. The iconic Akashi Kaikyo Bridge – until this year the longest suspension bridge in the world – punted on installing a second deck for future rail to reduce costs during construction. This lack of foresight means an underwater tunnel may be the only viable option between Honshu and Awaji.

Another variant is to run the Shinkansen not through Kobe but Wakayama south of Osaka and connect to Awaji. This allows the Kansai International Airport – Japan’s second busiest airport – to have a Shinkansen station which directly connects to Shikoku.

Politically and demographically, this satisfies three of the four prefectures (Kochi is the one left out) and connects the island’s most populous cities. However, cost of construction – especially with a brand new underwater tunnel now required – are expected to be exorbitantly high, discouraging the viability of this plan.

Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen

This is considered the pragmatic proposal. Unlike the horizontal orientation of the first proposal, the Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen is a north-south proposition. The proposal’s greatest strength lies in the Seto Ohashi Bridge where JR Shikoku already operates the Honshi Bisan Line. The bridge is capable of adding a second set of tracks for a Shinkansen, doubling its capacity to and from Honshu Island by connecting to the existent Shinkansen station in Okayama.

Once the Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen crosses into Shikoku via Seto Ohashi Bridge, the plan is run straight south to Kochi. Local trains from Matsuyama and Takamatsu will likely connect in the proposed central station of Shikoku-Chuo Shinkansen Station.

The project is expected to have a much lower cost and a much quicker construction time. However, politically, this has received a chilled reception, as it is now mainly Kochi Prefecture benefitting greatly from a one-seat Shinkansen ride while other cities require a local line transfer to the Shikoku Shinkansen.

A Blend of #1 and #2

In a show of political compromise, the alliance formed to bring a Shinkansen line by mixing the first two proposals. The Shikoku Shinkansen will connect to Honshu via the Seto Ohashi Bridge and to Okayama and will terminate at Kochi Station. However, this plan includes two branched lines to connect to Matsuyama on the west and Takamatsu and Tokushima in the east.

Politically, this is a perfect compromise as it satisfies all four prefectures equally and saves relatively some money and some time. However, the extra branches without capacity to connect to Kyushu on the west or Awaji and Osaka on the east leaves much to be desired and can be perceived as a wasted opportunity.

***

No action has been taken to propel any of the three proposals forward. Considering construction of a Shinkansen extension takes at least 10-12 years after another decade of planning, it seems unlikely we will see a Shikoku Shinkansen prior to 2050 barring unprecedented governmental urgency.

Closing Thoughts

In February this year, the transport ministry formed a panel to review and consider new ways to replace unprofitable railway lines in rural areas with bus operations. The panel will consider tax incentives and subsidies for companies, including JR companies, who replace these rail lines with bus routes.14

As JNR railways were privatized in the late 1980s, officials set the barometer for replacing an unprofitable line with bus operations at 4,000 average daily passengers per kilometer on a rail line. Once a rail line fell below this mark, they were to replace train service with buses. But this barometer has proven insufficient: after peaking in 1991, total train passenger volume in Japan has fallen by 20 percent. Now 57 percent of all train lines in Japan fall below the 4,000 daily passenger per kilometer barometer.15

As rail ridership has declined across Japan (outside major cities), so has frontline staffing in railway companies. More than half of all national rail stations in Japan currently have no staff to maintain and help customers as railways have cut into labor costs to balance its books. Over the past twenty years, the number of unmanned stations has increased by 10 percent. The increase in unmanned stations have led to accessibility concerns from disabled riders and a litany of customer complaints nationwide.16

Two prefectures with the highest ratio of unmanned train stations are under JR Shikoku: Kochi ranked first with 159 stations, or 93.5 percent of all its stations, having no staff. Tokushima ranked second with 62 stations, or 81.6 percent. (Tokyo, as contrast, only has 9.9 percent of its stations unmanned)17

Unmanned train stations and unprofitable rail lines seem like surefire symptoms of a railway in terminal decline. While the Japanese government has been aiding JR Shikoku’s fiscal woes, the recent ministry panel may signal a change in fiscal approach as all six JR companies are in the red due to the pandemic and require government assistance. Dark clouds of austerity are gathering. As absurd as it may sound, for the first time in its history, JR Shikoku may need to cut rail lines in lieu of bus operations.

The situation in JR Shikoku reflects a far somber outlook on the state of Japanese rail. As with many developed nations around the world, the rural-urban divide in Japan is becoming more acute. As Tokyo and Osaka receive more Shinkansen lines and state-of-the-art technology, an island a stone’s throw from Osaka is running mostly empty trains on unmanned stations around the clock. That island is desperately hoping for a single Shinkansen line to be its infrastructural savior. Salvation likely will take decades to materialize.

JR Shikoku is a fascinating business case as it provides an alternative outlook rarely explored when discussing privatizing nationalized railway companies: what if they fail? Not every privatized company is JR East with the luck of running the immensely profitable Yamanote Line. Perhaps free market darlings can point to JR Kyushu, whose clever business approach and long-term strategy led to full privatization and profit-making. But in the end, what is left in place once a service as integral as passenger rail fail? Dare we imagine a quarter of big Japanese islands without the level of passenger rail excellence the world expects when they think of Japan?

The latter hypothetical opens up a question which animates me personally as I think and write about these topics: what does it mean to have a national rail network? In the United States, much have been discussed surrounding the future of Amtrak and the utility of connecting more rural parts of the country via rail instead of better connecting the big cities together. In the 2020s and beyond, will this a zero-sum proposition? Perhaps the global answer lies in Shikoku and however its future unfolds.

https://books.google.com/books?id=bzRen1dcdTwC&pg=PT51&lpg=PT51&dq=shikoku+body+and+four+faces&source=bl&ots=wegPX3ARae&sig=ACfU3U2eHn6GS90u_XBjVYpbJE1sVFbhzQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-vOukpvT3AhX3iI4IHYmXDiUQ6AF6BAgyEAM#v=onepage&q=shikoku%20body%20and%20four%20faces&f=false

JR Shikoku’s FY 2019 financials https://www.jr-shikoku.co.jp/03_news/press/2019%2011%2008.pdf

https://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr60/pdf/45-51_web.pdf

JP Rail.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c10195/c10195.pdf

https://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr60/pdf/45-51_web.pdf

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://www.nippon.com/en/news/yjj2020122301209/

https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14549127

Ibid.

https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/13935358

Ibid.

Do you plan to write about the other JR companies in the future? I'd be curious what your take would be on JR Hokkaido, who is getting a shinkansen in the next few decades...

May I suggest some of Professor Michael Hudson's writings, he covers the disastrous effect of the Plaza Accords and following neo-liberal financialization on Japan.