Urban Paradise Lost?: The History of Seoul's Only Planned City

Why are residents of an urbanist dream so mad?

Two thousand years ago, two princes came from the north looking for new land fit for a kingdom. On the south bank of the Han River, they found one so. His older brother, however, wished his city closer to the sea, so he headed west where the river met the sea. But he soon found it unsuitable and went back to his younger brother in defeat. The younger brother took the throne and named his new city Wirye. His new kingdom, Baekje, would last for more than 700 years.

Wirye is alive again two thousand years later — as a glitzy real estate project on the southeastern edge of Seoul. Wirye New Town (위례신도시) is the first and only planned development built from scratch within Seoul’s city limits. Gleaming with glassy high-rise apartments and verdant parks, it now houses 120,000 people, many of whom own apartments units priced in at more than $1 million USD. Many Wirye residents receive a royal treatment as one of most desirable demographic in contemporary South Korean society: young, wealthy homeowners with jobs in Gangnam looking to raise a family.

Then, how did it all go so wrong?

Homeowners in Wirye are mad as hell. Broken promises over a 17-year period on new rail connections have left Wirye residents bereft of mass transit and left stewing in isolation and frustration. A volatile housing market and supply shortage has discharged an air of panic for relatively new homebuyers. They hold near-weekly protests in their town square and in front of Seoul City Hall demanding action.1 In 2024, Wirye residents took the drastic step (in non-American terms) of suing the Seoul city government.2 Wirye is now often shorthand for everything wrong with Seoul’s red-hot market among Korean real estate content creators. A cursory online search of Wirye New Town showcases the following headlines: “Wirye New Town collapse: My whole savings is about to disappear”; “Tears in Wirye New Town: What do I do, asks investor”; “Wirye homeowners say: ‘The government scammed us.’”3 45

But on the ground, this rancor may be hard to imagine. Wirye New Town on the surface looks like an urbanist’s dream: dense, high-rise sky-rise residential complexes circle an inner central business district (CBD) marked by a car-free promenade; two manicured parks, with a lake each, sandwich the town; and a “Human ring” walkway connects the parks and create a walkable, bicycle-friendly greenbelt. Conceived in 2008 and first move-ins in 2013, Wirye New Town was built as the model suburb for the model Korean family in the 21st century. Wirye was where the kind of smart, dense, walkable, mixed-use urbanism envied by many outside Korea and East Asia was actually achieved. (Take a stroll in 4K video below)

For Korean readers or those who lived in one of Seoul’s many satellite cities, this sole focus on Wirye may be confusing. Wirye is no more unique, perhaps even less stellar, than the other planned development which orbit Seoul: why not focus on the hyper-futuristic Dongtan suburb, or the pioneering Bundang district, or even Sejong, the new administrative capital of the country? They too have tall apartments and verdant parks and good schools. But I argue what sets Wirye apart is its shortcomings, and its shortcomings reveal a surprising amount on the current state of the South Korean political economy often hidden to Western observers.

This post, I hope, aims to achieve four objectives: 1) examine how in South Korea a new city is planned and built from scratch; 2) shed light on the criticality of rail transit in the success of these new developments; 3) explore the unique characters of the Korean housing market and the forces at play which both contribute to Wirye homeowners’ mutiny and the greater Seoul’s severe housing crisis; 4) ponder Wirye’s self-selected long history and its uncertain future. Many of these topics — planned city developments, the housing-rail linkage, and global housing dynamics — are topics of great interest around the world, including in my home California. (Remember California Forever?) Wirye New Town offers a rare opportunity to explore these complex ideas through one history, one full of promises and failures.

How to Build a City from Scratch

The first planned city in South Korea was created in 1962 under the Park Chung-hee regime at Ulsan, 30 minutes drive north of Busan. Purposed as a base for heavy industry in South Korea’s rapidly growing economy, Ulsan was designated as a special industrial zone, as corporations such as Hyundai and the Korean National Oil Corporation built there refineries, a car manufacturing plant, and a modern shipyard. Ulsan was to be home for these skilled workers and their families. Ulsan set the precedent of the Korean government’s priority in leading the selection and guidance for brand-new cities to be built by large construction corporations.

As Ulsan grew from a fishing village to a port town, Seoul grew exponentially into a megalopolis. As the political, cultural, and economic heart of the country, Seoul’s population grew tenfold from 1 million in 1953 to 10 million 1988. Seoul was where Korea’s first large apartment blocks were constructed. With the advent of the Seoul Metro, Seoul cannibalized marshlands south of the Han river, slums tucked away between mountains in the northeast, and textile factories in the southwestern plains to build large housing complexes to keep up with an explosive housing demand. At the same time, Seoul was building its first four Metro lines which zig-zagged the city. The government felt more drastic action was needed.

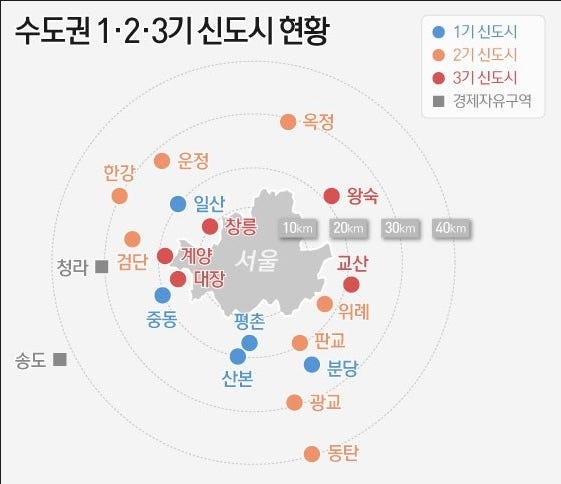

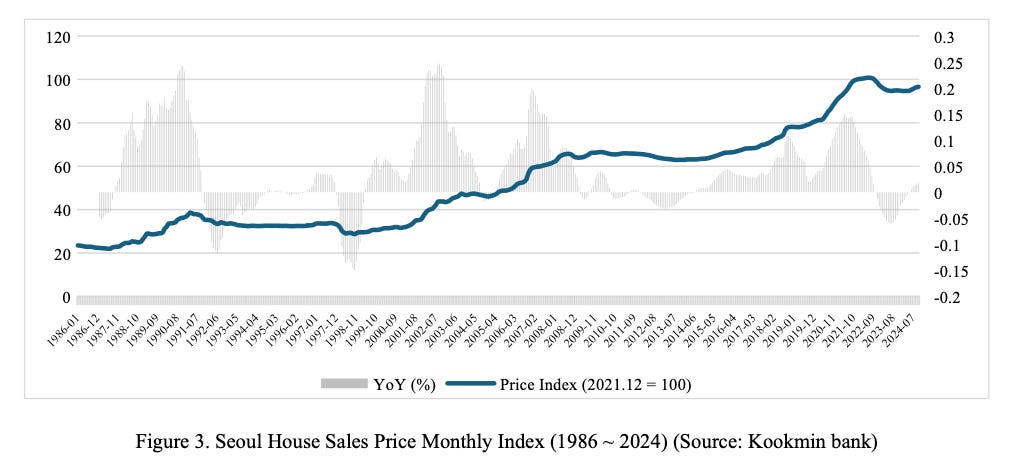

Twenty-seven years and two republics later since Ulsan’s creation, President Roh Tae-woo in 1989 announced the first generation of five new planned satellite cities to fulfill his campaign promise of 2 million new housing units. While suburbs like Bundang and Ilsan became its own centers of gravity within Seoul’s urban-suburban solar system, the first generation left only a minor dent on the housing demand. In 2003, under Roh Moo-hyun (no relation to previous Roh), Wirye New Town was announced as one of eight second-generation new planned cities. In the mid-2000s, Seoul housing prices soared at record levels, and the Roh government felt imperative to intervene; perhaps this urgency is a factor why the new generation was located further away from Seoul and transport planning was not as in lockstep with housing production as the first generation.6 A decade later, under another surge in housing prices, a third generation of five planned cities, more in style of the first generation, was announced in 2018.

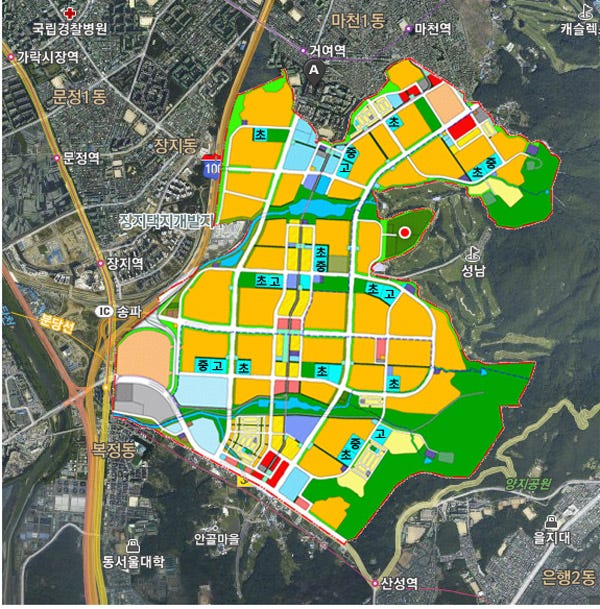

As the isochrone map above show, Wirye New Town is the only second generation city in direct contact with Seoul’s borders. To add, a third of its town is directly within Seoul as part of the southeastern and affluent Songpa District. This high distinction has been a blessing and a curse. Wirye administratively is split between Seoul in the north and its satellite municipalities Seongnam in the south and Hannam in the northeast, requiring a tripartite government over its affairs. Despite the pristine appearance, this fractured governance has created a Frankenstein-style planned city of bizarre inconveniences. Local development regulations such as floor area ratios differ based on the city of construction. Amenities such as schools, social centers, post offices, and bus routes are largely segregated between the three Wirye parts.7 Garbage bags and taxi fares cost differently depending on what part of town you are in. Wirye residents living in the City of Hannam have to pay a toll on the expressway around Namhan Mountain to visit their own City Hall for paperwork.8 The only thing the three cities seemed to have agreed on is agreeing to name their portion Wirye to promote the brand and pump up property values.9

Before the first shovel for Wirye New Town hit the ground in 2008, the Korean government went out its way to clear the road for a successful development. They granted a 10-year lift of all greenbelt regulations starting in 2009 allowing unrestricted housing heights and limits in previously undeveloped areas in the fringes of Seoul’s borders.10 The government also relocated existing military bases, including a previously undisclosed U.S. army base, and military schools to clear the land. They also funded infrastructure work to improve road transportation prior to construction. Under the original 2003 plan, Wirye New Town was a centerpiece of the liberal Roh administration’s plan to massively increase affordable rental apartments to the Seoul region in the nearby suburbs. However, after a power change to the conservatives in 2008, that plan seemed to have been scrapped for the more lucrative home-buying endeavor. Wirye New Town became a homebuyer-majority area. In 2022, only 22% of its 42,700 units were rentals compared to 73% of stock available for purchase.11

Wirye New Town is composed of 52 high-rise apartment complexes and mixed-use developments. Every residential complex is planned out by the state-run Korea Land & Housing Corporation (commonly called “LH”) which solicit bids from construction conglomerates, such as Samsung, Daewoo and Hyundai. A total of 27 construction companies claimed at least one Wirye complex as its own for construction, including the Ministry of National Defense which built apartments for soldiers. For LH, Wirye is one parcel to a nationwide portfolio of “Smart Cities” totaling 950,000 housing units with the goals of achieving the government’s housing goals and providing a consistent source of housing availability.

Due to its newness and proximity to Gangnam, Wirye saw its housing prices balloon steadily from its first housing sale in 2014 to 2016, when residents settled in and businesses opened in the CBD. Apartment complexes in the Seoul area of Wirye expectedly were the most desirable but remained consistent all three administrative sides. Wirye’s housing price peaked in 2021: a 35 pyeong — or a 1245 sq ft apartment, a common medium-size apartment in Korea — on the Seoul side peaked around 1.7 billion Won, or $1.24 million USD.12 At that time, Wirye homeowners had every reason to believe the prices were only going to go up.

Waiting for a Train

When building 42,700 housing units to house 120,000 people on land the size of two New York City Central Parks, transport inevitably becomes the major talk of town.13 Most apartment complexes come replete with underground parking lots, but the only desirable mode of transport for these commuter is the train, especially ones heading straight into Seoul. This desire has been the source of much ire.

As shown in the administrative map above, two Seoul Metro lines skirt past Wirye. Wirye nominally has a Metro station of its own called South Wirye (Nam-Wirye), but it sits outside its borders; from the central square, it takes 30 minutes to walk from the town square. Another station, Macheon, is a longer distance away on the north side. As it stands, Wirye residents have to choose either to walk or bike a fair distance to a Metro station, or brave the infamous Gangnam traffic on a bus or on their own to commute to Seoul.

Wirye is the black sheep of its siblings. Among the eighteen total planned cities across three generations, Wirye is the only one without a direct rail access to Seoul or a direct rail line to Seoul under construction. As noted earlier, the second generation cities were planned further away and more clumsily in regards to matching transportation planning with housing planning. It is ironic that the only planned cities in Seoul’s city limits does not have such critical amenity. Planned cities in the northwest of Seoul are connected via the Gyeongui commuter line and now GTX-A high-speed regional rail, which opened in 2024. Even those without direct rail access now have a clearer path to one in the near future: two new third-generation cities east of Seoul have the GTX-B line and an extension of a nearby Seoul Metro line in the plans to give them a direct rail connection Wirye residents have been begging for.

Since Wirye’s very conception, three plans have been floated to bring much-needed mass transit access to its city center: a new Metro line connecting Wirye to Gangnam; a new peripheral Metro line connecting Wirye to a nearby satellite city; and a tram line connecting to the two existing Metro lines on its north and south sides. All three were announced as the transportation solutions back in 2008. Seventeen years later, none of them have materialized.

Of the three, the most anticipated and frustrating wait has been the 15-kilometer long Wirye-Sinsa Line, the one-seat train ride to Gangnam in 15 minutes. The plan was approved by LH in 2014, just in time as residents began moving in, and the project was awarded to Samsung C&T Corporation to begin construction. However, Samsung forfeited its bid in 2016 citing low profitability concerns. Four years later in 2020, a new consortium led by GS Construction won the bid to build the Wirye-Sinsa Line by 2027. GS initially stalled in its planning phase due to internal infighting over where to finalize station locations along the lucrative Gangnam neighborhoods. Then, of course, COVID shut everything down. The project slipped through GS’s grip when the pandemic triggered high inflation and high interest rates.14 Two years later, the Russian invasion into Ukraine hit the Korean construction economy hard, and that was the knockout punch to GS’s bid. By the time GS pulled out, the Wirye-Sinsa Line was projected between 1.5 ($1.1 billion) and 1.8 trillion Won ($1.3 billion), its price tag more than doubling from GS’s 2020 projection of 830 billion Won.15 Without a private contractor to build, Wirye residents have been desperately trying to pressure the government to do the construction work themselves to no avail.

The second Metro proposal called the Wirye-Gwacheon Line was originally as an outer loop line around the southeastern periphery of Seoul, connecting Wirye to the satellite city of Gwacheon to its west.16 It was set to complete in 2013 when it was announced in 2008.17 Seventeen years later, in May this year, LH unveiled a revised map of the Wirye-Gwacheon Line as a Y-shaped three-legged line, with the third leg extending to Gangnam. However, the plan does not extend to Wirye at all. In the new revised proposal, Wirye has been left out of its own namesake line — with the closest station some distance outside its town limits.18A spokesperson for the Wirye citizen’s group demanding rail connection expressed his frustration, saying “we will gather our forces to respond to this wrong route plan is not confirmed.”19

But not all is lost for Wirye. The tram is happening, and, yes, under construction as we speak. For Korean railfans, this Wirye tram line is one of great intrigue, as this is the first tram line in Seoul since its once-expansive tram network closed for good in 1968. For longtime residents, however, it feels too little too late: after no private bidders in 2014, the Seoul Metropolitan Government took it upon itself to build the line with public money. Construction began in 2022 and the 12-station, 4.9 kilometer line will connect Macheon Metro station to the north to Nam-Wirye Metro station in the south through the car-free central promenade. The project has cost 261 billion Won ($189 million) and will open in 2026.20

In the past year, Wirye residents have ratcheted up their protests to air their rail grievances. Their main gripe is toward the Seoul Metropolitan Government for their transportation slow-footing, despite all homeowners having to deposit a 7 million Won (about $5,000) dedicated toward transportation improvements in the area. A total of 310 billion Won ($224 million) has been contributed by Wirye into this pot.21 And for what exactly? Time is running out, it seems, for Wirye’s home-owning class.

High-Rise, High Stakes Housing Crisis

For the western reader, it may come as a surprise, even a shock, that a city full of high-rise apartments is enduring a severe housing crisis not unlike those in San Francisco, New York City, or London. One may know of the housing surfeit in nearby Tokyo — thanks to its similar aesthetics and capital city status — and apply it clumsily to Seoul. But housing political economy in Seoul is complicated, capricious, and behaves in many ways unlike Tokyo, and this section hopes to unpack several of its layers.

There are three good starting points to understand Seoul’s housing crisis which impact homeowners and rentiers alike. First, South Korea remains a heavily heliocentric country with Seoul as its sun and its gravity unrelenting. Since the 1980s, government efforts have tried to diffuse (with satellite cities) and break (a la Sejong City) Seoul’s hegemonic status as the political, economic, and cultural city in South Korea without equal. It has been largely ineffective. The Seoul Metropolitan Area occupies less than 12% of South Korea’s land area but 47% of all housing stock and 51% of population.22 Whereas Seoul’s housing price saw a 3.6% year-over-year increase between 2024 and 2025, the next five biggest cities in South Korea outside of Seoul’s orbit saw a negative dip in housing prices.23

Second, nearly 40% of total households in Seoul are now single-person households, driving up demand for individual housing units that far outpace the volume of existing housing stock, many of which are 2- or 3-bedroom family-oriented units.24 Young Koreans in Seoul are increasingly marrying later or choosing to live alone, its downstream effect reflected in South Korea’s notorious birth rate. Nearly half of the 1.7 million registered single-person households in Seoul are in their 20s and 30s. Limited availability in land in and around Seoul and financing to build smaller units better suited for single-person households have driven up competition for these newly premium housing units. Per the Korea Housing Institute, housing demand in Seoul outpaced supply in 2023 by more than 200,000 units — despite a 6% population decline in Seoul between 2015 and 2022.25 26

Third, the post-COVID economic volatility and inflation which exploded transit construction costs, as evidenced by the unbuilt Wirye-Sinsa Line, has likewise impacted housing construction in Seoul. In 2021 and 2022, housing prices grew at near-record highs until the Bank of Korea continuously raised interest rates to cool the red-hot housing market; meanwhile, the central government loosened housing restrictions to foster a supply boom.27 In 2023, the boom skidded to a freeze, as prospective homeowners could not afford mortgages at its highest interest rates since 2008. Local governments outside Seoul put a halt on construction as thousands of newly built units sat empty.28 Even in red-hot markets like Seoul, private developers struggled to secure financing under high interest rates, stricter loan conditions set by the government and higher construction costs. In 2024, housing construction permits met only 32% of Seoul’s annual target for housing supply.29

Where does Wirye fit in all this? The three factors listed above are conditions more acutely felt by lower-income single-household renters across Seoul and its suburbs. In contrast, Wirye is a homeowner enclave for upper and upper-middle class family households. Take the aforementioned 35 pyeong apartment on the ritzy Seoul side of Wirye, which was priced in 2021 around 1.7 billion Won ($1.24 million). After a 20% drop in housing price in 2023 alone, the same unit has crawled back up to 1.55 billion Won ($1.13 million), recouping half of its lost value. Wirye, like nearly all parts of Seoul, has seen an upswing on its property values, and with the advent of the Wirye tram, there is room to be optimistic. But the mood on the ground from homeowners is very dark and cynical. How do we make sense of this divide?

I would like to shed light on three more factors which apply exclusively to the real estate-owning class of South Koreans that may share some insight on their unique personalities and dilemmas. First, owning housing or real estate is not only critical to a Korean household’s wealth generation; it may as well be the only way. Per Bank of Korea data, 65% of net assets of Korean households are tied in real estates whereas only 7% are in stocks; in comparison, the net holdings of households in the United States divide to about 28% in real estate and 33% in stocks.3031South Korea’s financial exposure to real estate nearly doubled between 2014 and 2024, with loans to households making half of the added amount.32 The Bank of Korea voiced concerns over the extreme over-reliance of household investments into real estate, warning of a bubble. Both liberal and conservative lawmakers have urged Koreans to invest more into stocks and bonds, a tall task in a country still traumatized by the Asian financial crisis of 1997.33 34

Second, residential real estate investments, especially high-rise apartments, are a ticking time bomb. Built modularly, rapidly and sometimes haphazardly, even the shiniest, newest high-rise apartments in Seoul do not age so gracefully. Apartments older than 20 years often show leaks, cracks, sewage smells, and icicles in wintertime.35 Apartment passed 30 years is considered obsolescent. In Korean real estate, the 30th birthday of an apartment building means it’s time for a “reconstruction” — either via heavy, even total, renovation or a clean demolition-rebuild project. In 2024, LH announced apartments can just begin reconstruction as soon as it hits 30 years without a safety diagnosis test, which historically served as the first step toward reconstruction.36 What once were new, modern apartments in Seoul in the 1990s have been “slumified” — to use a Korean English loanword — through wear and tear as it nears the dreaded 30th birthday.37 Under these timelines, homeowners expectedly calculate their home equity with a far shorter frame than those in the United States, where a prewar era home is often viewed increasingly desirable. Homeowners naturally look to cash in on their home equity before the buildings show age in its 20s and obsolescence in its 30s. Any later can mean their chance at cashing out melts away. It then may be of note to remind viewers that first apartments opened in Wirye New Town 13 years ago.

Third: while hard to quantify, there is a real, deep, longstanding paranoia among Korean homebuyers of getting ripped off or being swindled by a broker, landlord, or some other party. Real estate corruption scandals are very common and extremely high profile. They litter the annals of modern South Korean history and rise to the very top. In 1995, President Roh Tae-woo was arrested and sentenced to life for taking more than $300 million in office — most notably, a slush fund from a construction magnate to sell illegally land at Suseo, near Gangnam, to build housing complexes. In 2022, the Daejang-dong real estate scandal — located in another planned city outside Seoul — shook the Presidential race against liberal candidate Lee Jae-myung, handing Yoon Suk-yeol the closest election victory in modern Korean history.

Landlords, while never popular, has reached new lows of trust in recent years. The jeonse deposit system — where tenants deposit a lump sum worth a year or two rent’s worth to their landlord for very low rent or free rent for the lease’s duration — has been the cornerstone of the home-renting system in South Korea since the end of the Korean War. It was made ubiquitous in the 1960s and 1970s when interest rate and savings rates were very high and mortgages were uncommon. For example, the average jeonse deposit for a Seoul apartment in 2022 was 680 million won, or $522,000. (Imagine saving that much money just to rent!) For tenants, jeonse is often a stepping stone toward home ownership and has been preferred over the more conventional monthly rent system common in the West (wolse). Jeonse landlords typically invested these deposits into more real estate, a practice known as “gap investment”; this gap investment and its high, somewhat predictable profits, were what kept the jeonse system firmly in place in the Korean socioeconomic fabric.38

However, during the real estate freeze in 2022 and 2023, many jeonse landlords found their real estate portfolio too exposed and could not pay back their tenants’ deposit when their lease ended. In several cases, the expanding jeonse crisis exposed many scammers who fled with their tenants’ jeonse deposits. For many, these deposits were the tenants’ entire life savings built painstakingly over decades. It hit those in their 20s and 30s the hardest, and the psychological damage was catastrophic. At least eight people committed suicide after being victimized in the jeonse scams of 2022-2023.39 This jeonse crisis greatly shook the confidence of both renters and homebuyers and bred paranoia about who people can trust in the market.

To make matters worse, even the regulators are sometimes implicated: in 2021, suspicions swirled that LH employees preemptively bought land before the government’s announcement of the third generation of planned cities and became a months-long front page news saga.40 Suspicion and short-term speculation continue to fuel real estate news. In March, acting President Choi Sang-mok vowed to take “all available steps” to curb speculation in the housing market, perhaps reflecting the current frenzied zeitgeist of home buyers and sellers.41 It also breeds downstream, bleeding down to neighbor-to-neighbor relations. Per one report, rental tenants in Wirye have been questioned by their neighbors about their housing status and derogatorily labeling other neighbors as renters.42

I find the Korean real estate market fascinating as they seem to intersect what is commonly understood to be opposite dynamics of housing politics: large volumes of dense, high-rise apartments and the highly speculative commercialization of housing as an investment vehicle. In the United States, at least, the quality that often appreciates housing value is its detached form, on a plot of land not directly in touch with any other unit. That quality does not apply in South Korea, where apartment is king. And yet the same specter of housing price speculation is alive, perhaps at a more frenzied pace than in the United States. That speculative economy has allowed neighborhoods like Wirye to boast $1 million-plus housing units — figures seen commonly in the United States — in an economy where average household annual salary is $46,800 — only 60% of that in the United States.43 Unique factors, as outlined above, hopefully can help understand Wirye and Seoul’s housing market and make sense of its many contradictions.

Wirye: Where Past and Future Meet

It seems remarkable how many random history factoids Wirye New Town ties to itself through geography. First, it rests against Namhan Mountain to its east, providing an easy mountain hike getaway to its locals. More than 400 years ago, this mountain was where the Joseon king laid siege and then surrendered in humiliation to invading Qing forces. (An excellent movie on this event is available on Netflix). Second: the north side of Wirye is an abandoned golf course, once the playground of an undisclosed U.S. Army base which has been around since the 1950s. To make room for Wirye New Town, the Americans left. Korean regulators found in the golf course large quantities of carcinogens and oils, such as arsenic, left unabated; this was discovered after an elementary school was built next door.44

History abounds in Wirye. Even if it was just a cheap marketing ploy, Wirye New Town ties in 2000 years of Korean history, spanning the Three Kingdoms era, the Joseon era, and the postwar US-backed era in one small locale. It carries potential for more history-making. In June, Lee Jae-myung was elected President of South Korea. In 2023, prosecutors indicted Lee on corruption charges, alleging Lee, as Seongnam mayor in the 2010s, colluded with private property developers on projects in and around Seongnam — including Wirye New Town.45 Lee still faces trial on this indictment even after his election.46 There remains a small, though unlikely, chance Wirye New Town may be back on the news to reshape Korean history once more.

History is often personal, and this is where my personal history intersects with Wirye’s. Like Lee Jae-myung, I lived in Seongnam in the 1990s. My parents moved our family to the then-new planned city of Bundang where we lived in a high-rise apartment. That apartment and its surrounding environs is where I hold some of my first memories quite dearly. As perhaps one does about important locations in the making of one’s childhood, I wistfully regard that Bundang apartment was the finest place I ever lived. In nostalgic reverie, I looked for the apartment and its history and its present and its future, which, along the way, I found another suburb, this time on the edge of Seoul, to weave another history of.

https://v.daum.net/v/20250516122105446?f=p

https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/12/03/UMZVRX4TEJGKZHVWFZQPG7MTSI/

https://www.hankyung.com/article/2025051270876

http://keia.org/sites/default/files/publications/feb%2007.pdf

https://namu.wiki/w/위례신도시#s-5

https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2023/11/19/PU6QCRFCCRFSPOVRPQYKRXOCQ4/

https://n.news.naver.com/mnews/article/079/0002710512?sid=101

https://realty.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2024/11/06/2024110601099.html

https://cafe.naver.com/jaegebal/3946092?art=ZXh0ZXJuYWwtc2VydmljZS1uYXZlci1zZWFyY2gtY2FmZS1wcg.eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJjYWZlVHlwZSI6IkNBRkVfVVJMIiwiY2FmZVVybCI6ImphZWdlYmFsIiwiYXJ0aWNsZUlkIjozOTQ2MDkyLCJpc3N1ZWRBdCI6MTc0Nzk4MTIyNDMxNn0.9YiQoxe2rG-0KDGwmnVXGDe2uzmMt4C1McPi32i7lg4

https://m.blog.naver.com/taeho0210/223107095352

Wirye’s surface area is 6.77 square kilometers. Central Park’s surface area is 3.41 square kilometers.

https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/06/12/ZQPOHDQTFRAJBAWCGTRUBUDVQU/

http://www.hanamilbo.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=10115

https://ethankim1.tistory.com/entry/위례과천선위과선-노선도-착공-개통시기-수혜지역-연장노선안

https://www.kyeonggi.com/article/20250420580109

https://www.mk.co.kr/news/society/11310339

https://news.nate.com/view/20250311n34932

https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/12/06/F2SJ5RJTJZG2PMUXRC5JOJLN4M/

https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/06/12/ZQPOHDQTFRAJBAWCGTRUBUDVQU/

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/158888/Park-zoeyp311-msred-cre-2025-Thesis.pd

https://www.globalpropertyguide.com/asia/south-korea/price-history

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/158888/Park-zoeyp311-msred-cre-2025-Thesis.pd

https://www.chosun.com/english/national-en/2024/01/24/MUVLZBCNVVG6HDXMHZZ3XU2NKI/

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/158888/Park-zoeyp311-msred-cre-2025-Thesis.pdf

https://www.globalpropertyguide.com/asia/south-korea/price-history

https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/02/07/business/industry/housing/20230207175620058.html

https://www.mk.co.kr/en/realestate/10997419

https://www.mk.co.kr/en/stock/11216119

https://www.reuters.com/markets/wealth/us-stock-market-pushed-household-wealth-record-high-fourth-quarter-2025-03-13/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.kedglobal.com/real-estate/newsView/ked202410130001

https://www.mk.co.kr/en/stock/11216119

https://www.kedglobal.com/real-estate/newsView/ked202410130001

https://koreaexpose.com/korean-apartments-shoddy-quality-finally-get-attention/

https://www.mk.co.kr/en/realestate/10918342

https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/24092326

https://www.blueroofpolitics.com/post/the-coming-financial-crisis-of-failed-jeonse-rents/

https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240527-debt-suicide-fraud-south-koreans-hit-by-real-estate-scams

https://www.inhapress.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=9660

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-19/south-korea-moves-to-curtail-rising-speculation-in-home-market

https://www.hankyung.com/article/2025041498776

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/economy/20240417/average-korean-household-earns-3900-monthly-shinhan-bank-report

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-korea-indicts-opposition-leader-lee-over-property-graft-2023-03-22/

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/legal-challenges-facing-south-koreas-incoming-president-lee-jae-myung-2025-06-03/

It's beyond maddening to see construction of rail projects in SK take so long--in particular, I find the seemingly-new and yet very common insistence on undergrounding railroad projects to be very frustrating, and more than a bit confusing.

I grant that Korea's urban form and transportation paradigm isn't Japan's, for a long list of reasons that I don't need to explain to you. However, you look at the planned routes of things like the Wirye-Sinsa line, and they parallel extremely wide roads. Why not build elevated and save on costs, and build them faster? I know, too, that Korea might then have to contend with public opposition to this and it might not be any faster (nor consequently any cheaper), but it is possible, in any case.

Pair that with things like the perennial push to underground the Gyeongbu line throughout Seoul, and I can't help but wonder why--given the plethora of successful domestic examples of rail-oriented development--Korea is so insistent on burying its rail, given all the downsides.

35 years ago a friend who was married to a Korean started to tell me about Korean Real Estate, Marriage Dowery, etc. Back then all I could think was "Something wicked comes this way." It was like Das Capital and Life in Feudal Europe had a baby. Now that baby had (a) baby(ies).