The Death and Privatization of Japanese National Railways (Part 1, 1949-1982)

How does a train agency rack titanic amounts of debt?

Two JNR staff hold the Japanese National Railways’ flag in 1970. (Source)

In my previous post, I examined the birth of the Japanese National Railways (JNR) and the conditions from 1945 to 1949 which greatly shaped the visions and more importantly, the limits, of JNR’s administrative powers. The American-led Supreme Commander for Allied Powers (SCAP) sought an autonomous, politically robust and financially sustainable JNR public corporation – in the mold of the New Deal-era Tennessee Valley Authority – with strong labor unions as its muscle. But during negotiations in 1948, SCAP’s vision for an autonomous JNR was stripped away by the Japanese political establishment which took advantage of a SCAP increasingly distracted by the spectre of rising communism in Japan (especially in the labor movement) and East Asia.

JNR’s first decade after its birth in 1949 was wildly successful. JNR enjoyed comfortable profits and increasingly high ridership through the 1950s and the early 1960s. In a postwar Japan simultaneously recovering and setting new standards of postwar economic prosperity, JNR effectively held a land transportation monopoly in both passenger and freight travel. It was during this time JNR leverage its profits and land monopolies to rebuild and expand its rail network at breakneck pace. Electrification of its major trunk intercity lines was completed in the 1950s. In the rapidly growing Tokyo region, JNR invested billions of Yen to expand its train throughput and capacity on five critical trunk lines. In the late 1950s, JNR proposed a new intercity train service to connect Tokyo and Osaka in record time: the Tokaido Shinkansen.

In 1964, the same year JNR opened the Tokaido Shinkansen ten days before the Tokyo Olympics, JNR recorded its first major fiscal deficit. JNR management assured this would be a one-time blip.1 The deficit grew slowly the next few years then exploded in 1968. Any private corporation would have been well liquidated before 1970, but the public JNR soldiered on as it bled profusely every year. After JNR’s multiple failed internal reforms in the 1970s, cries for accountability and administrative reform sparked a niche elitist movement which sped through a staggering pace. Under such momentum, the monolithic JNR was dissolved and split in 1987, its expansive trackage and massive train fleets split between six regional (and one freight) private Japanese Railways (JR) companies.

Most prosaic explanations diagnose JNR’s downfall in an Edward Gibbons-esque prose: a bloated, rotten, bankrupt public entity corrupted by lazy union workers hastened the need for radical change in the neoliberalism-crazed 1980s. But this has always been too juvenile a history, wholly unable to capture the velocity and weight of the collapse. Economic narratives work better; JNR lost its land transportation monopoly as both passenger and freight transportation slid in market share to private automobiles and trucks. By 1970, cars and trucks would surpass railways in transportation market share, and JNR was unable to overcome their market share decline. But the broad strokes miss out on the fine details.

This two-parter aims to explore not only the progression of that narrative but plug holes. Readily available explanations rarely explain how JNR’s debt ballooned to the size comparable to sovereign nations (its cumulative deficit mark hit the 20 trillion Yen, or roughly $87 billion in 1981 USD, mark); why the debt crisis got this bad; where exactly JNR failed in its revenue earning capabilities; where and when the privatization movement began; and how such a movement was achieved in a few years.2 Other public national railways in developed nations have their flaws but none have been dissolved into history like JNR. What made this case so exceptional?

It is the emphasis of this post to prescribe the death of the 38-year-old Japanese National Railways as a political murder, ranging between a mercy killing and an assassination depending on your sympathies for JNR and its conditions. As JNR became insolvent in the 1960s, the Diet and the Ministry of Transport – the two final arbiters of JNR’s annual budgets – refused to allay the situation until the 1980s. Despite attempts at internal reform, JNR was at the whims of Diet politicians who used it as an open check for their own easy political wins. Starting in the 1970s, a small group of politicians, bureaucrats and academics pushed for administrative reform across all of government but only through political savvy was JNR targeted in the open as the sacrificial lamb at the altar of neoliberalism in the 1980s. It took a wily, experienced Prime Minister once derided as the “weathervane” to make the JNR privatization his signature political achievement come true.3

In this history of the dissolution and privatization of JNR, we delve into the conditions which fostered the administrative reform movement, the motivations of the reformers, the gradual blossoming of the movement, and the political and media influences which effectively sealed victory for the reformers. The JNR privatization was, as one observer put it, was a “coup d’etat within the court”: a revolution inside the bounds of civil government.4 Understanding this history will either elicit admiration or disgust based on your personal political leanings. It also may elucidate what it takes to realize such a change, how to do it and exactly how much is transferable to other countries – should one want it so.

Author’s Note

When discussing the issue of privatization in passenger rail on a national scale, proponents often point to the stellar success of JR as proof of transferability. JR, indeed, has been a favorite example neoliberals point for the success of privatization. The discourse, however, can only remain shallow without understanding a more comprehensive history of its predecessor, JNR. This is the second of a multi-part examination of JNR’s history, and aforementioned, a critical timeline and history in understanding both the fall of JNR and birth of JR.

To accomplish this work, I rely heavily on two English-language papers found online: University of Stirling academic Ian Smith’s 1996 study “The Privatisation of the JNR in Historical Perspective: An Evaluation of Government Policy on the Operation of National Railways in Japan” and Ohio State University academic Eunbong Choi’s 1991 study “The Break-up and Privatization Policy of the Japan National Railways, 1980-87: A Case Study of Japanese Public Policy-Making Structure and Process.”

As with all previous S(ubstack)-Bahn posts on Japan, I welcome all feedback, including corrections, to any facts listed in this article. I do not speak Japanese and acknowledge I am working with a fractional amount of literature on this topic only available in English. In fact, in the months of research, reading and writing, I can sense there is much literature in Japanese on this topic that is not easily available to an English speaker in the United States. But nonetheless, thanks to the written works of Smith and Choi, I feel compelled to explore and examine to the best I can. I consider this — and all I write on S(ubstack)-Bahn — to be incomplete, amateur histories for myself and others to build upon, not to settle as gospel.

The Emergent Debt Crisis

On October 1, 1964, the Tokaido Shinkansen opened to the world’s awe as the first bullet train in the world. The Shinkansen reduced a trip from Tokyo to Osaka which took nearly seven hours by more than half at just over three hours. Opened just 10 days before the start of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the Shinkansen was Japan’s grand proclamation to the world that a prosperous, high-technology post-war Japan had arrived.

In 1964, Japanese National Railways, the builder and operator of the Tokaido Shinkansen, marked its first deficit since its foundation in 1949 at 30 billion Yen. Its worst previous lossmaking year was 1955 at 183 million Yen, but a 226 million Yen profit the next year quickly erased the deficit and related concerns.5 Despite a much higher 30 billion Yen deficit, the Japanese government in 1964 regarded it as a “temporary phenomenon.”6 The Diet – who gives final approval to JNR’s operating and capital budgets – clearly was not fazed: in 1965, the Diet approved JNR’s Third Five Year Long Term Plan which included capital investments of 1,420 billion Yen, including for the Commuting Five Directions Operation to fix Tokyo’s rail congestion problems.7

1964 was a long time coming. Through the 1950s and 1960s, its market share of passenger and freight travel has slipped to the private automobile and truck, respectively. In 1950, JNR commanded 60% and 52% of Japan’s passenger and freight travel market shares, respectively; by 1965, the shares slipped to 45% and 30%.8 Private automobiles by 1965 made up 35% and 26% of the market share in passenger and freight travel. Cars and trucks would surpass railways in this race by 1970.

JNR’s 1964 deficit was accumulated mainly from the increasingly unprofitable operations in the local passenger and freight services connecting rural towns and villages distant from rapidly growing cities. It should be noted that the Tokaido Shinkansen, JNR’s shiny new toy, did not add to this annual deficit. The Tokaido Shinkansen project broke ground in 1959 with a 159 billion Yen budget, made entirely of government loans, railway bonds and a low-interest $80 million loan from the World Bank. Largely due to the sharp price increases in land acquisition, the Tokaido Shinkansen’s budget doubled to 380 billion Yen – the extra burden of which were paid with more loans.9 Nevertheless, the Tokaido Shinkansen was an instant financial success and would remain JNR’s most profitable golden goose in generating rail-related revenue, even after future Shinkansen lines came into service.

Increasingly unprofitable local passenger lines, especially on the main Honshu Island, mushroomed in trackage. JNR was obligated by the Diet to operate additional railway lines being built in rural areas with little wiggle room for the corporation to give feedback or object. In 1951, the government established the Railway Construction Council to manage railway construction on behalf of the national interest. For the next thirteen years, the Railway Construction Council ordered JNR to construct 80 new railway lines – in mostly rural areas – which JNR would have to operate indefinitely.10 This Council had 29 members but only one was a JNR representative. Perhaps more egregiously, the 80 new lines were determined using a plan for a comprehensive national rail network set in 1922 – a whole generation before World War II and the total postwar reshuffling of Japan’s demographics.11

In 1964, the government replaced the Railway Construction Council with the Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation to allow the latter to provide funding for railway construction projects in both the public and private sectors.12 The Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation however worsened JNR’s position, as it directly funded new railway constructions which JNR would have to operate. Under the previous Council, JNR were still able to make objections to newly planned railway lines and offer revisions. This mechanism, however lacking to JNR’s bottom line, was stripped away with the arrival of the new corporation. As Smith notes with the new corporation, “the Diet effectively removed the impetus of JNR opposition to the continuation of the policy of building lines which even at the outset were known to be unprofitable.”13 Adding salt to the wound, Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation continued to use the 1922 framework to lay out future new lines all the way into the late 1970s. By 1980, when the practice was stopped under the new JNR Reconstruction Act, rural routes accounted for 40% of JNR’s total trackage but only 5% of its ridership.14

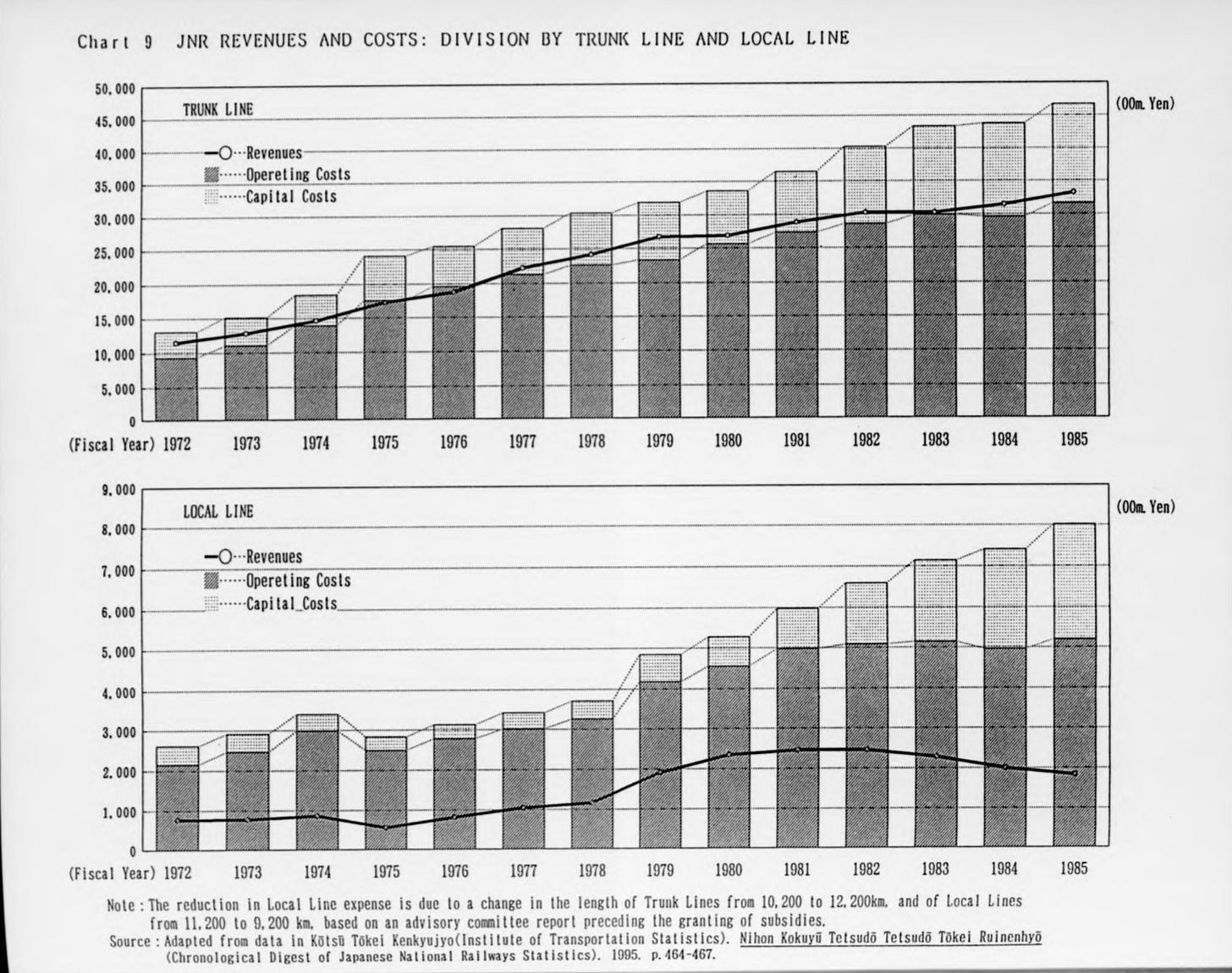

Chart of JNR Revenues and Costs, divided between the trunk lines and local lines. Source: Ian Smith’s “The Privatisation of the JNR in Historical Perspective: An Evaluation of Government Policy on the Operation of National Railways in Japan.”

In 1966, JNR reported an operating loss of 123 billion Yen, four times the loss it reported in 1964.15 JNR’s reserves were obliterated. Had it been a private company, JNR would have declared bankruptcy and been liquidated with such a loss. JNR’s capital budget was similarly obliterated in 1967, when JNR’s financing scheme for the Diet-approved Third Five Year Long Term Plan collapsed, leaving JNR responsible for a mountain of high-interest bonds. In 1965, JNR issued large amounts of railway bonds without a government guarantee to fund the plan after Ministry of Finance disapproved entrance to its government-backed Fiscal Investment and Loan Program (FILP).16 The Ministry of Finance effectively balked at the huge spike of annual investments requested by JNR compared to past years, and JNR went its own way to raise funds. Within two years of issuance, JNR was reduced to “issuing tokubetsu (special) bonds to meet the interest payments on its railway bonds.”17 While the national government began to provide subsidies to ease the capital debt burden starting in 1969 (the operating subsidies would come to rescue in the 1970s), researcher Nobuo Takahashi writes this financing scheme failure as the “direct cause” of JNR’s bankruptcy and downfall. 18

Despite the alarming consecutive years in the red, the Diet pressed for expansionary spending from JNR throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was financial prudence thrown out the window, but it was sound politics within the contours of the Liberal Democratic Party, which maintained a one-party rule in Japan since 1955. The first decades of LDP’s big tent coalition was founded upon a high and ironclad rural turnout. Keeping its main rivals the Socialist Party at arm’s length from power, the Dietary LDP sought to score easy political wins for their rural or small town constituency, and the path of least resistance often was a new or improved JNR rail line. Many elected LDP members were retired senior bureaucrats who were intimately close to their successors and well-versed in party machine politics.19 The elitist, incestual Japanese bureaucracy which the American occupiers in the 1940s worried would consume Japanese politics turned out to be prescient.

Under hypnotic political influence despite heavy hemorrhaging, JNR from 1969 to 1973 proposed more spending. After the premature end of the Third Five Year Long Term Plan in 1968 (and the financing scheme disaster), JNR’s new Reconstruction Plan in 1969 called for the construction of the Tohoku Shinkansen, connecting the northern half of Honshu Island to Tokyo.20 In its 1972 Corporate Plan (scrapped before put into action) and 1973 Reconstruction Plan, JNR sought to match the ambitious tone of new LDP Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka, who in June 1972 proclaimed the remodeling of the Japanese archipelago, with new industrial centers away from Tokyo and Osaka and huge infrastructural projects to deliver prosperity to Japan. 21New Shinkansen lines would be the crown jewel to connect Tanaka’s Japan and expand the “National Railway Empire”; JNR proposed plans in the Reconstruction Plan for 11 new Shinkansen lines, including the Joetsu Shinkansen which would connect Tokyo to Niigata – Tanaka’s beloved hometown.22 Unlike the Tokaido Shinkansen, Tohoku and Joetsu Shinkansen would prove to be instantly and incredibly unprofitable operations once it opened for revenue service in the 1980s. Their opening would only accelerate JNR’s exponentially growing deficit figures in its final years.

JNR’s acquiescence was not due to a lack of effort. In 1968, JNR management proposed to close a large number of its unprofitable local lines, but they were rebuffed by the Ministry of Transport.23 In its deliberations for the Five Year Long Term Plan in 1965, JNR proposed the ability to issue domestic bonds of its own and a revision of the tariff rate to be able to raise passenger fares and freight rates to balance their manageable debt. Both were struck down by the Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, citing concerns of escalating inflation.24 (Not to mention the Ministry of Finance rejected JNR's request for government-backed FILP bonds en masse, per Takahashi) Concerns were raised inside JNR and outside sources in the early 1970s to scale down JNR’s rapidly unprofitable freight operations but was swiftly ignored by the JNR Board and, more importantly, the Diet who were fully committed to Tanaka’s expansionary and industrialized remodeling dream.25

For Tanaka, his Dietary LDP, and JNR, the dream would come crashing down in the Oil Shock of 1973. As the second largest importer in the world after the U.S., and one whose petroleum supply was wholly imported, the Oil Shock profoundly shook the Japanese economy.26 The government was suddenly strapped for capital, and a real estate boom – partly caused by Tanaka’s bold proclamations – collapsed.27 The Japanese economy went into a recession, as did much of the developed world. The Reconstruction Plan was scrapped in less than a year. JNR missed yet another stop for reclamation.

The Asahi Shinbun newspaper on a passenger riot on April 25, 1973 at Akabane Station in Tokyo. The photo shows a train lit on fire. The riot was sparked by frustrated riders impacted by JNR unions’ slow-down strike. The article also writes a total of 26 JNR stations were vandalized and destroyed by similar riots. (Source)

The Reform Circus

By 1969, the fifth consecutive year being in the red, JNR was ready to take action to fix itself. From 1969 until 1980, JNR proposed a total of seven reform plans to do just that. None of them made any inroads toward solvency; the deficit would continue to spiral. If anything, the most impactful proposals would harm JNR’s relationships with two closest allies: unionized workers and the national ridership.

In 1969, JNR made its first reform attempt in the only manner they knew then: expanding its network and increasing investment to combat the rising market share of private automobiles. The plan was soon scrapped, as was the 1972 Corporate Plan and the 1973 Reconstruction Plan. After the 1973 plan was scrapped due to the Oil Shock, only then did JNR management muster the courage to abandon its expansionary pitches and look toward rehabilitation by reducing its workforce, requesting sustainable sources of government subsidies and limiting its expansions.28

In 1975, the fourth reform plan proposed workforce rationalization and more government aid but also with a 50% increase in passenger fares nationwide. The fare increase was allowed after the government finally relaxed its tariff rate controls after nearly two decades of suppressed fare increases. Repeated Diet pressures to keep fares artificially low as part of its domestic economic policy contributed to very affordable fares lagging far behind annual inflation rates. A sudden, 20-year-high jump in fare prices angered riders and depressed JNR’s ridership as choice riders in larger metropolitan areas opted for now-cheaper private railways (they were adjusting fares accordingly in the same timespan) or resorting to use of private automobile. To keep up its debt obligations and catch up to the rate of inflation, JNR running under relaxed tariff controls increased passenger fares between 4% and 16% and freight rates — despite transport volumes virtually collapsing behind the truck industry in the 1970s — between 3% and 10% every year from 1978 until 1987.29

The reforms targeted inside the house as well. Arguably the most important reform plan of the 1970s was the Productivity Increase Movement (Marusei Undon), a multi-year effort declared by management to reduce labor waste, improve productivity and synchronize management-labor relations. The main objective for the movement was to offload much of a 430,000 strong workforce which was aging and soon in need of pensions — something a destitute JNR had little reserves to fund.30

The Productivity Increase Movement’s legacy, however, was the destruction of most remaining goodwill between management and the labor unions – and among the various JNR labor unions themselves. A new moderate and pro-management labor union Tetsuro emerged during this time period and rapidly expanded due to its acquiescence to the Productivity Increase Movement and warm relationship to management.31 The pre-existing unions, Kokuro and Doro, were radicalized by a hostile management and Tetsuro’s concurrent moves to alienate and fracture their labor front. Between 1973 and 1975, unions held illegal slowdowns and walk-outs to protest against its management.

Riders across Japan did not handle the sudden disruptions well; during the March 1973 slowdown, enraged commuters stranded at Ageo Station in suburban Tokyo rampaged and destroyed the station, took hostage the stationmaster and stoned the unmoving trains.32 A month later, another slowdown strike led to 26 stations being vandalized and destroyed, with an undisclosed amount of trains set on fire. Popular discontent against JNR unions for these actions began to brew from these impacts, and such bitter memories would prove to be a powerful source for anti-public corporation sentiment during the lead-up to JNR privatization in the 1980s.

A video on the 1973 train riots above

Starting in 1977, the government began relaxing many of its fiscal restraints put against JNR for almost 30 years. The Diet relinquished its controls on the tariff rate altogether and ended restrictions on investments outside the mainstream railway business in 1977. In 1980, the JNR Reconstruction Act passed by the Diet finally released JNR from the obligation to help construct and operate new rail lines and abandoned the 1922 framework used to plan new, unprofitable rail lines in rural areas.33 Also in 1980, the JNR Management Improvement Plan was drafted with the intent to establish a fiscally sound JNR operation by 1985. The days of JNR’s expansionary modus operandi were over, albeit very overdue. The delay would prove indeed too late; the 1980 plan would be the last reform plan from JNR to fix its finances before its privatization seven years later.

By the late 1970s, a national disillusion had set in among elite bureaucratic circles on Japan’s economic direction. Japan’s public finances was dangerously over-reliant on government bonds by 1980, with nearly a third of Japan’s total revenue met with money raised by national bonds. The Ministry of Finance warned it as an emergency.34 Government spending rocketed in the 1970s, as its welfare state grew in volume largely to accommodate medical and pension costs to an aging population. Select bureaucrats and academics looked abroad and towards a new economic movement called neoliberalism and sought to import that to Japan. Some adopted the slogan “Financial Reconstruction Without a Tax Increase” to begin the push for neoliberal-flavored administrative reforms to correct the state’s course.35

The administrative reform movement had been born in the late 1970s, but it had no tangible agenda and no target in its early years. But things soon would break their way: as the 1980s unfolded, the movement’s leaders were rather catapulted into strategic positions of influence deep inside the state to push for their reforms. After their ascension, they needed a target, a white whale, for their movement’s growth. The JNR, bloated by its titanic debt, looked like an easy kill.

The Wheels Turn for Big Change

It must be stressed that despite JNR’s 20 trillion Yen deficit by 1983 – which at the time was equivalent to national debts of at least two South American countries combined – JNR’s day-to-day operations were not impacted in any meaningful manner.36 Even with the ugly explosions of labor strife in the mid-1970s, JNR was highly popular and its workforce still carried the spirit of pride working for the national railways, a tradition carried over from before World War II.

Despite the struggling rural lines and a decline in transport market shares, JNR through the 1960s and 1970s maintained the high level of service frequency, cleanliness and organization renowned internationally to this day. It is evidenced by the continued growth in ridership in the Tokaido Shinkansen and its trunk lines, mainly between and in the Tokyo and Osaka metropolitan areas. Smith writes that the post-privatization accounts of attributing JNR’s demise to its falling quality of life are mere revisionism: (bold for emphasis)37

It is ironic, therefore, that the picture painted of worsening labour relations, and of conflict between management and the unions – used later by the pro-JNR reform movement shold have produced, in reality, relatively little disruption to rail services. Whatever other sins of remission can be laid at the door of the JNR, the failure to maintain regular, prompt and efficient train services was manifestly not of them. There were commuter protests…but, in the main, the level of service provided to the public was kept at a level of which any other national railway would be immensely proud. In any case, the number of disruptions had already started to decline dramatically, several years before the administrative reform process moved into action. It remains a moot point, therefore, whether the reform policies were formulated in relation to the reality of the state of labour relations in the JNR in the early 1980s, or in line with some image of strife and conflict which by then was not supported by fact.

The administrative reform movement entered the mainstream as a vague government promise during a snap Diet election in 1980. Liberal Democrat Prime Minister Masayoshi Ohira died of a heart attack during the campaign, and the LDP rallied around Ohira’s death to win back a Diet majority. Ohira’s successor, Zenko Suzuki, was keenly aware of the growing desire to hold unelected powerful bureaucrats accountable and of concerns over Japan’s overly reliant bond financing. Suzuki pledged to resolve the public financing crisis with reforms the public can trust.38

In November 1980, the Second Ad Hoc Administrative Reform Commission (or Second Rincho, as both Smith and Choi calls it) was created and held deliberations the next year. In its first report to the government, the Second Rincho called for welfare cuts to its next fiscal budget; JNR was hardly mentioned.39 As Second Rincho continued to convene, the focus turned to bureaucracies and public corporations where the committee can find recommendations for improvement. Soon, the Second Rincho locked eyes on the three public corporations, known as San Kocha, as a package to cut fat and subsidy reliance: Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT); Japan Tobacco and Salt Public Corporation; and the Japanese National Railways.40

After the first report, the Second Rincho in fall 1981 split into four subcommittees to diversify and narrow from its broader aims of administrative reform to more direct and tangible reforms. The Fourth Subcommittee would focus on the San Kocha as a whole and would soon become the only subcommittee worthy of intrigue.41 At its inception, the subcommittee’s aims were more at the NTT and the Japan Tobacco and Salt Public Corporation, as its overseeing ministries commanded little power and more pliable to outside change and recommendations from the subcommittee.42 But as the subcommittee delved in its discovery phase, its aim to reform all three public corporations would quickly narrow to a full-throated offensive to privatize and split JNR. This quick pivot would prove possible because of a handful of men coming together for, even in early 1982, just five years before privatization, a mere political pipe dream.

The influential and octogenarian businessman Toshio Doko. (Source)

All the Prime Minister’s Men

Two men at the helm of the Second Rincho and the Fourth Subcomittee steered the ship. Toshiwo Doko was appointed by Prime Minister Suzuki to chair the Second Rincho. Doko was the former President of Federation of Economic Organizations (Keidanren), Japan’s largest and most powerful big business association. Doko was ardently pro-business and anti-taxation and came into his new appointment with a “telling conviction” that reform without taxation was the tonic which would spur new prosperity to the nation.43 His leanings were reflected in the Second Rincho’s composition, as business interests and a journalist from the right-wing newspaper Nikkei Shinbun created the majority over labor union delegates.44

The contours of privatization began to take shape under the Fourth Subcommittee and its chair Hiroshi Kato, who reported to Doko. Kato, a professor at Keio University, sought to compose his subcommittee free from bureaucratic interests; only five of the 16 members were former and current public sector employees.45 While Kato himself was initially not convinced of privatization for JNR, his subcommittee included academics with an extensive record advocating for privatization or criticizing JNR’s freight business model.46 The Fourth Subcommittee submitted its first report in April 1982, submitting – for the first time in any reform group so far – recommendations to privatize and divide JNR into sectional companies.47 Three months later, the subcommittee submitted another report, officially confirming its stance for the first time that JNR be broken up.48

JNR’s board and upper management’s reaction at the time was opaquely muted and delayed in public, but internally it clearly showed a “high degree of complacency and lack of concern” according to Smith.49 They also seemed to be rather unaware of enemies already inside the gate. Three mid-level executives, eager for reform, would covertly work with Doko and Kato to pressure JNR for systemic change and soon lead an internal campaign to dissolve JNR. Known as the San Nin Gumi (Group of Three), the three executives did not believe the 1980 Management Improvement Plan would succeed and held a longstanding antipathy toward JNR labor unions.50

While the San Nin Gumi were nominally part of a larger pro-reform faction inside JNR, the three conspirators took things further. In an early-stage senior management meeting to discuss how to respond to the Second Rincho, the San Nin Gumi proposed to their higher-ups the dissolution of JNR and dismissal of all its employees to start over and then left their seats. After the theatrics which shocked JNR senior management, “there were no organized, calm discussions within the JNR concerning what the future national railway should be like,” according to a former JNR executive.51

The San Nin Gumi also worked to influence the ruling Liberal Democratic Party to their privatization agenda. To match the alarming pace at which Kato’s Fourth Subcommittee moved forward, the LDP in February 1982 launched its own subcommittee to explore the issue of JNR reform from the Party’s perspective. Much of the LDP apparatus was vehemently opposed to any JNR reform; they were worried any reform would impact the web of “vested interests” which materially benefitted railway management, Diet politicians, and construction and supply companies.52 The San Nin Gumi, however, were quietly influencing and conspiring with the subcommittee chair Hiroshi Mitsutaka by feeding him inside information. The working relationship needed to be covert, so Mitsutaka and the three executives would often meet at nights at the Imperial Hotel in central Tokyo so documents can be drafted for the subcommittee.53

In June 1982, a month before the Fourth Subcommittee’s July report, the LDP Mitsutaka Subcommittee submitted its own report, concluding that systemic changes, including privatization, should be supported on the condition that the 1980 Management Improvement Plan would not succeed. The conclusion shocked much of LDP’s leadership and rank-and-file, as it crossed the Party’s unofficial line and sided with the Second Rincho. With alignment between the reformist-minded Second Rincho and ostensibly the LDP, the ammunition — at least in the working papers department — to privatize and split JNR was fully stocked. After the July report from the Fourth Subcommittee officially calling for privatization, preparations immediately began to form a JNR Reform Commission (which would begin the next year) to dictate the recommendation into law. In September 1982, the Suzuki government announced firm plans to reconstruct JNR within five years.54

The announcement is a very long way from where Suzuki must have imagined when he created the Second Rincho in November 1980 to stamp his approval to the popular but nascent administrative reform movement. Within two years, privatization of JNR (and the NTT and Japan Tobacco and Salt Public Corporation) emerged from a pipe dream to a serious proposal. However, at the end of 1982, such ideas were still constrained mostly in committee meetings, lacking the political muscle to push it over the finish line. Suzuki – who faced constant Cabinet instability due to LDP factionalism – stepped down in November 1982. The next Prime Minister would need to expend huge personal political capital and navigate a still-murky political landscape to accomplish what, even in 1982, must have been seen still as improbable.

Smith, Ian. “The Privatisation of the JNR in Historical Perspective: An Evaluation of Government Policy on the Operation of National Railways in Japan.” The University of Stirling, 1996, p. 211

Choi, Eunbong. “The Break-up and Privatization Policy of the Japan National Railways, 1980-87: A Case Study of Japanese Public Policy-making Structure and Process.” Ohio State University, 1991, p. 2

Smith, p. 342

Choi, p. 306-307

Smith, p. 188

Smith, p. 211

Smith, p. 207

Smith, p. 167

Smith, p. 169-170

Smith, p. 170

Smith, p. 207

Smith, p. 207-208

Smith, p. 208-209

Smith, p. 214

Takahashi, Nobuo. “Japanese National Railways’ Financing Schemes and Bankruptcy.” Annals of Business Administrative Science, 2019. p. 268

Takahashi, p. 272.

Takahashi, p. 266.

Choi, p. 162

Smith, p. 213

Smith, p. 215-216

https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00115/

Smith, p. 209

Smith, p. 211

Smith, p. 216

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,943510-1,00.html

https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00115/

Smith, p. 218

Smith, p. 219

Smith, p. 233

Choi, p. 243-244

https://www.nytimes.com/1973/03/14/archives/tokyo-commuters-go-on-a-rampage-bands-roam-the-rails-five-are.html

Smith, p. 223

Choi, p. 65

Choi, p. 6

Smith, p. 336

Smith, p. 253-254

Smith, p. 341

Smith, p. 349

Smith, p. 343

Smith, p. 354-355

Smith, p. 351

Smith, p. 348

Ibid.

Choi, p. 413

Choi, p. 416

Smith, p. 356

Ibid.

Smith, p. 362

Smith, p. 371

Smith, p. 366

Smith, p. 369

Smith, p. 372

Smith, p. 357

Wonderful summary. Thank you. I spent many happy hours on Japanese trains in the 1960s.

super compelling, rigorous read!