"Hell Line": Lessons from Seoul's controversial privatized subway line

A dive into Seoul Metro's Line 9

A normal pre-COVID rush hour crowd on Line 9, from a Korean Broadcasting System report in 2019 (screenshotted)

In the innumerable debates about public transit in North America, many panaceas are offered but none more than a slogan solution: privatize the public transit agencies.

It’s a silver bullet which acts like catnip for its supporters. The idea goes: public transit agencies – outdated, bloated and/or lazy – need some free market innovation and competition to do what’s best for the riders. The support is commonly backed with Japan’s history of privatization of its national railways and its privately-owned subway lines in Tokyo (lots of caveats with how truly “private” Japanese rail really is), and its great success since. 1It’s a well-worn one-two punch.

Less discussed, however, is Japan’s closest neighbor and its dalliance with privatized mass transit. South Korea sought to capture lightning in a bottle for its newest subway line in Seoul in the 2000s. Planned and built through some of Seoul’s densest and richest neighborhoods in the late 2000s, the new Line 9 opened in 2009 with all the bells and whistles (i.e. 100% accessibility, platform screen doors, express tracks), the high ridership demand necessary for success and the newest rolling stock available in South Korea. Unlike Japan’s current public-to-privatized rail networks, Line 9 was built from scratch, funded and operated entirely by private conglomerates. Line 9 was set up for success, at least as well as any private venture outside Japan can be.

So how did things go so wrong?

In its first 12 years, Line 9 has gone from newest attraction to black sheep of the sprawling Seoul Metro system. Pre-COVID overcrowding levels became so dangerous it shocked the media, government and the most thick-skinned Seoul commuters alike. The Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) had to step in to bail out, threaten or do both to rescue Line 9 and its riders multiple times. Its employees detailed to the media horror stories of abuse and overwork to keep Line 9 moving with a threadbare workforce. Since COVID-19 pandemic, Line 9’s finances are in tatters with an uncertain future.

Line 9 is often better known for its nickname: “Hell Line.” (지옥철; ji-ok-cheol) How did Line 9 earn its ignominy?

Methodology and Background

In July 2020, I wrote a Twitter thread on this topic, following the news of Seoul Mayor Park Won-Soon committing suicide shortly after allegations of years-long sexual harassment of his secretary was revealed.2 He was known as a big advocate for public transit in Seoul, and for me, his shocking death was the entry point into the rabbit hole that is Line 9 and its myriad issues. The thread has been auto-deleted, and this post is a recreation and expansion on that deleted thread.

I consider this post an aggregation of Korean reporting spanning a decade and translating into English. There is no original reporting on my end. The sourcing is almost all in Korean, my mother tongue. I will list all sourcing as best as I can, all from media outlets in South Korea (of both left and right political leanings) I have vetted and determined as legitimate.

Hopes for the “Golden Line”

Line 9 was formed out of simple geographic demand. Line 9 would run south of the Han River, connecting Gimpo Airport, the second most used airport in Korea to the west of Seoul with the southeastern district of Gangnam, the wealthiest area for Seoul and headquarters of Korea’s global soft power hegemony. Line 9 would also make stops at the National Assembly and Seoul’s Express Bus Terminal, among others, and provide transfers with other Seoul Metro lines.

Hand-drawn map of Seoul Line 9, its different phases and landmarks important to Seoul and Line 9’s riders.

It was, as a 2012 report from the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism puts it, the “Golden Line” for Seoul.3

In 2002, the first phase of Line 9 went into construction. The early 2000s were an economically uneasy time in South Korea, who was emerging out of its 1997 financial crisis which hard-crashed its hyperactive economy.4 From 2005 to 2007, the city of Seoul, under conservative Mayor (and future President) Lee Myung-bak, began negotiations to create a privately-owned franchisee to operate the first phase of Line 9 under the name Seoul Metro Line 9 (SML9) Corporation, according to the Seoul Institute, a think tank employed by the city of Seoul.5

SML9 was built by various conglomerates from around the world. A consortium of construction companies led by Hyundai-subsidiary ROTEM Group would build the rolling stock for Line 9.6 Operations were split 80/20 by the French company Veolia Transport and ROTEM Group.7 The overall project was financed by a consortium of Korean and foreign investors, led by the Australia-based Macquarie Group.8 Line 9 would remain private for the first 30 years of operation, until at least 2039, in the conglomerates’ agreement with SMG.9

Infographic of Line 9’s rolling stock, manufactured by ROTEM Group (Source: Seoul Metro Line 9)

Line 9 opened in July 2009 to great ridership demand. In the first 6 months of operation the average daily ridership was 148,000.10 By 2012, the ridership increased to 227,000 and for the first time began to outpace the estimated ridership demands made prior to the line’s opening.11

With ridership beginning to outpace predicted demand, the cracks began to show. Trains during rush hour slowly turned into bedlam with commuters fighting to cram themselves into train cars. Personal space became impossible for thousands of riders every day. The rider experience turned hellish.

Birth of the “Hell Line”

An investigation from the Korean Broadcasting System in 2015 discovered Line 9 trains at its busiest peaked at 238% of accepted train car crowding levels.12 In KBS’s study, 160 riders in a single train car were determined as 100% crowding levels, with every seat taken plus two riders by every door and three riders on every section of the middle aisle. Line 9’s 238% rate meant a single subway car would carry 368 people in one car during peak hours. (A Line 9 subway car’s dimensions are 19.5 meters in length and 3.12 meters in width, or in American terms, 64 ft by 10.2 ft)13

Such levels pushed the limits on what a train car can physically carry. The closest Seoul Metro Line in peak crowding levels was Line 2, at 208%, 30% less than Line 9’s. Despite other 8 lines traveling greater distances and stopping at many more stops, the average congestion levels for all 8 lines were at 158%.14

An infographic from KBS calculating the crowding levels at top table (the two rows are number of riders and crowding levels by percentage) and illustrations of what different crowding levels can look in a subway car.

How was SML9 caught so unprepared for overcrowding so early in its operation?

Multiple Korean media reports traced a major error to two studies done by transportation researchers commissioned by Seoul Metropolitan Government and the Ministry of Transportation to estimate Line 9’s future ridership demand. In 2000, researchers estimated 2014 daily ridership to be around 370,000 – which was very close to its actual 2014 ridership of 384,000. However, in 2005, another study was published and lowered the 2014 daily ridership figures by 37% to 240,000, vastly underestimating future ridership on Line 9.15

The 240,000 riders estimate carried massive implications for how the Seoul Metro Government and Line 9’s financiers were to prepare for Line 9’s future. During its negotiations in the mid-2000s, the city was hooked into a minimum revenue guarantee (MRG) for Line 9’s first 15 years of operation; if the new subway line failed to balance its operating costs with its generated revenue, SMG was obligated to fill in the deficit.16 Under an intense anti-tax burden political climate in the 2000s, SMG was incentivized to conservatively estimate future ridership figures in hopes it will expect less MRG burden, according to the Korean Economic Daily newspaper.17

Private financiers of Line 9 also used the conservative ridership estimates to cut costs wherever they can. Line 9 was already proving more expensive to construct than its predecessors for its inclusion of express service with extra tracks and rail equipment, and acquisition of the most expensive land in Seoul, according to Donga Weekly.18 The underestimated ridership predictions gave the financiers green light to reduce its rolling stock size from the original 186 cars (31 6-car trains) to 144 cars (36 4-car trains). As the other eight Seoul Metro lines operated 8-car trains, Line 9 began by running exclusively 4-car trains.

The financiers and operators also slimmed its frontline labor force by passing on including a ticket office and station office at Line 9 stations – unlike other Seoul Metro stations, which had both – and outsourcing maintenance for trains, elevators and other facilities. Operating personnel on Line 9 was 22 employees per every kilometer of rail, accounting for one-third the size found in Seoul Metro’s other lines.19

The cost-cutting measures built on deflated ridership expectations created dire experiences for its riders. Starting in 2012 until the outbreak of COVID-19 which deflated its ridership, all major Korean TV news networks covered the “Hell Line” experience with harrowing, claustrophobic videos of commuters packed into train cars.20 Seoul Fire Department began dispatching personnel on standby with defibrillators at Line 9’s busiest stations.21 One news network collected air samples from a rush hour train and found dangerous levels of carbon dioxide, levels high enough to make passengers faint or ill as they were not receiving enough oxygen.22

A demonstration of what 238% train crowding levels look like in another report from KBS in 2015 (screenshotted).

The City Goes to War with Line 9

Amid newfound infamy with crowded trains, SML9 in 2012 announced its next move to get in the public’s good graces: it would raise fares by up to 57% on Line 9.

Fares for Seoul Metro’s Lines 1-8 are dictated by the Seoul Metropolitan Government. Line 9, a private line, believed they were within their rights to arbitrarily set fare prices per a 2005 operations contract signed by former Mayor Lee Myung-bak.23 Whereas Lines 1-8 would set the adult fare to 1,050 Won (88 cents in 2022 USD), Line 9 proposed their single-ride adult fares at 1,550 Won ($1.30 in 2022 USD).24

Then-Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon went on the offensive against SML9. His SMG called the fare increase illegal, as Korean rail law dictated fare increases must occur within a range set by them and superseded the contract signed by Lee25. Park also called the fare increase unethical, saying the two-tiered fare system caused “great confusion” to Seoul citizens.26 Park said his SMG would revisit its minimum revenue guarantee conditions with SML9 and appoint an outside official to investigate allegations of preferential treatment to Macquarie Group, SML9’s biggest shareholders.27 If SML9 approved the fare increase, Park and SMG threatened to fine SML9 10,000,000 Won ($8400 in 2022 USD) for every day it was in effect.28

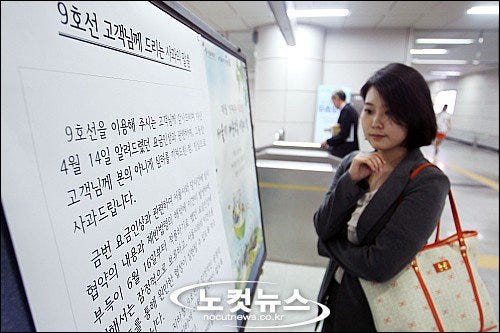

After a month of stand-off, SML9 finally backed down under Park’s aggression. In an apology letter posted on its website and on every station bulletin board, SML9 said the fare increase came from a confusion in interpretation of the rules.29 Park snagged a major victory over SML9, and his government soon exerted more influence on SML9. But what followed was not clarity but even more administrative chaos. Little to no immediate relief for the daily commuters crammed into train cars was on the way.

A Line 9 rider reads a public apology letter from SML9 posted on every station bulletin board after backing down on its fare increase proposal in 2012. (Source: NoCut News)

One Line, Two Owners, More Chaos

Major changes soon followed after Park’s fare increase victory in 2012.30 First, fare policy was clarified: only the Seoul Metropolitan Government can dictate fare increases for Line 9. Second, the minimum revenue guarantee conditions signed by Lee Myung-bak was replaced with a minimum cost compensation which greatly reduced Seoul’s burden on covering Line 9’s operating deficit. As a monetary olive branch for SML9, SMG introduced the “Citizen Fund”, a first-of-its-kind bond portfolio to which citizens of Seoul can invest into Line 9 and its future.

Third and most importantly, in 2013, Park led efforts for major restructuring on the financial side of SML9. Macquarie, the largest shareholder and dubbed by one media outlet as a “tax-eating hippopotamus”, and ROTEM group, the largest construction investor, sold all its shares to several Korean banks and left Line 9 investments altogether.31

The restructuring was a small reprieve for Park as both Seoul and Line 9 headed toward more trouble. Line 9 was to be extended further east as part of its long-planned Phase 2 expansion. Despite the hellish overcrowding in the current Phase 1 section, Phase 2 was set to open in 2015 with 5 new stations, with a Phase 3 expansion soon to follow. (Phase 3 opened eight more stations in 2018)

SMG desperately tried to add more trains to supplement Line 9’s undersized fleet to get ahead of overcrowding before Phase 2’s opening. In 2011, SMG procured federal government funds for Phase 2 four years ahead of schedule to buy 48 more cars.32 The next year, SMG went back to the federal government to ask for more money to buy more trains. But this time, they were rebuffed on a bizarre technicality.

While Line 9 is privatized for its first opened section, Phase 2 and 3 were to be owned by SMG (through an approved consignor who will handle daily operations) and become a public transit entity. This meant one subway line had two owners: one private, one public. The Ministry of Strategy and Finance, the federal lender to whom SMG requested for more funds, rebuffed SMG’s request by saying its investments are only for public projects and new train cars for Line 9 meant it would also benefit the privatized Phase 1 section.33 By that logic, unless the new Line 9 cars funded by the Ministry can only run on Phase 2 and 3, SMG was on their own to procure more train cars.

Then-Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon off boards a Line 9 supplemental bus provided by the city to allow fears of even more crowding on Line 9 trains (Source: Kyunghyang Newspaper)

Phase 2 opened in 2015 with much trepidation from the media and the public.34 Seoul provided free supplemental buses running along Line 9’s route when Phase 2 opened to allay public fears of an even greater rush hour crush. 35

With newly procured 48 train cars, Line 9 slowly began expanding from 4-car trains to 6-car trains, which did help with crowding. The process to expand all 6-car trains continued until 2019; however, many commuters and media voiced outrage yet again in 2019 on the “More Hell Line” as Line 9 reduced its popular express trains for more local lines, assuming erroneously that the increase in train cars can handle the crush.36

Even More Hell for Line 9’s Employees

Line 9 ran the most crowded trains in Seoul with the smallest workforce among all nine Seoul Metro lines. It is no surprise its employees were overwhelmed, but the allegations and numbers detailed in a 2017 article by the newspaper Hankyoreh paint a shocking picture of labor abuse and its medical repercussions.37

Train operators worked from 4am for 8-9 hours then back at 4pm for another 8-9 hours on a single weekend day

A train operator, Mr. Kim, slept 1 hour total in a span of four days and was removed from the cab. Overhead on the intercom, the interventioner told Mr. Kim “if you keep working, you will die. Getting you out is the way to keep you alive.”

Among 148 train operators in Line 9’s first nine years, 88 has left the company

From 2012 to 2017, 12 Line 9 employees were diagnosed with cancer. 4 employees in their 30s were diagnosed with thyroid cancer

Line 9 supervisors would verbally abuse employees if they took a vacation day on the same day other Seoul Metro lines held tests for prospective applicants

Two female train operators collapsed on the job

3 female employees reported miscarriages while working on the job; one reported two miscarriages

Labor unions representing Line 9 workers went on strikes in 2017 and 2019. In 2019, they demanded SMG help pressure SML9 to hire more workers and introduce a step-based salary system.38 During the 2017 strike, unionists demanded that Seoul Metropolitan Government not renew its Phase 1 operator contract with the French-owned operator RATP Dev, saying taxpayer money continues to flow into the coffers of foreign conglomerates.39 In 2019 (before the second strike), SMG agreed to this demand and did not renew its operator contract.40

Line 9 employees on strike in 2017, holding the sign “Hold the French corporations responsible!”

After 2019, new battle lines were redrawn surrounding Phase 2 and 3. While the two new phases are technically owned and operated by the city, SMG contracts the operations out to a private consignor in a 3-year contract.41 Since 2020, labor unions in and outside the transit industry joined in protest to demand SMG bring Line 9’s Phase 2 and 3 under Seoul Metro’s umbrella and ultimately convert all of Line 9 into a public-owned entity with stronger labor regulations. In 2020, unions threatened a “warning” labor strike to escalate its demand.42 But they suspended plans after Mayor Park Won-soon committed suicide saying it was “unbecoming” to strike after such a tragedy.43

Is Hell eternal? Line 9 during COVID

As with all major heavy rail lines around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 erased Line 9’s overcrowding concerns – a feat no previous rail car procurement or service improvements could resolve. In November 2020, Line 9 reported a 20% decrease in ridership (very good considering far more precipitous drops in other transit systems around the world). Line 9 requested the Seoul Metropolitan Government a bailout of 13,500,000,000 Won ($11,300,000 USD) to make up for COVID-related operating revenue losses which drew the ire of municipal finance watchdog organizations.44

Beyond continuous expansion to the east of Seoul, Line 9 has withdrawn further plans to expand its fleet. Considerations for expanding all Line 9 trains to 8-car trains – in line with the other Seoul Metro rolling stock – was turned down in 2020 as “economically unfeasible.”45

Personal thoughts and conclusion

I grew up in Seoul in the 1990s before coming to the United States, so I missed all of Line 9’s construction and operations. It took the suicide of a popular mayor to discover so much about Line 9. I do not dismiss the slim chance I may have blind spots about Line 9 due to lack of experience riding the subway line.

Even from afar, I believe Line 9 is a real-life example – from a very developed nation in the 21st century, no less – on the dangers of privatizing mass transit. I must admit now I work in public transit and hold biases against the privatization of what I believe is an essential public utility akin to clean water and electricity. But my research, which sources both left-leaning and right-leaning news outlets in South Korea, demonstrates a clear conclusion: the privatization experiment in Seoul has been a big failure.

Cost-cutting maneuvers, byzantine bureaucratic divides and miscalculations can often be found in public transit agencies, too. However, Line 9 shows privatization is not the solution against these errors; it can often exacerbate the same issues more acutely.

There is much written material on the virtue of privatizing public transit, but almost none from the other side exploring the pitfalls of privatizing public transit. My hope is this post can be a resource for those interested in this debate, along with a foreboding moral of the story: Be careful what you wish for. The road to hell is often paved with good intentions.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-10-31/why-tokyo-s-privately-owned-rail-systems-work-so-well

https://www.dw.com/en/south-korea-seoul-mayor-suicide/a-54119747

http://newstapa.org/article/Mu1xb

https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2006/cpem/pdf/kihwan.pdf

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

Ibid.

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1160110/000090342307000684/veolia-6k2_0709.htm

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

https://opengov.seoul.go.kr/mediahub/view/?nid=22105130

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

Ibid.

https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3050976

https://www.metro9.co.kr/site/homepage/menu/viewMenu?menuid=001004007001

Ibid.

https://www.hankyung.com/society/article/2015032908331

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

https://www.hankyung.com/society/article/2015032908331

https://weekly.donga.com/List/3/all/11/99158/1

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3050914

https://news.naver.com/main/read.naver?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=022&aid=0002809462

https://news.naver.com/main/read.naver?mode=LPOD&mid=tvh&oid=214&aid=0000652906

http://newstapa.org/article/Mu1xb

https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2012/04/15/2012041501413.html

https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/administration/529584.html

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2012/04/15/2012041501413.html

http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001730044

https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/3권_Metro_Introduction%20of%20Rapid%20Urban%20Railway%20System%20-%20Construction%20of%20Subway%20Line%209.pdf

https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/598777.html

https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3050914

Ibid.

https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/area/area_general/684093.htm

https://m.khan.co.kr/local/Seoul/article/201504081614091

https://www.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DlxOXR_4XEZQ&usg=AOvVaw3VyHF1fAK7FaZ74dxbNrF9

https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/821862.html

https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20191007002300315

https://www.edaily.co.kr/news/read?newsId=03188166616154256&mediaCodeNo=25

https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190118071051004

http://webzine.seoulmetro.co.kr/enewspaper/articleview.php?master=&aid=1783&sid=73&mvid=684

https://bizn.donga.com/3/all/20200709/101892650/2

https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/A2020071010190003703

https://news.sbs.co.kr/news/endPage.do?news_id=N1006065684&plink=LINK&cooper=YOUTUBE

https://www.hankyung.com/society/article/202010288743i

Hello - this is a really cool exploration. If you'd like to discuss it with me on the Korea Deconstructed podcast, feel free to get in touch (datizzard@swu.ac.kr)